Overview

The American Youth Policy Forum (AYPF) facilitated a series of 10 field trips around the country to provide state policymakers with an intensive professional development opportunity focused on policies and interventions that support high school redesign. Each trip was planned to highlight high school improvement strategies in a particular region—participants met with local policy leaders, educators, and students, as well as visit redesigned high schools. This project, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, supported the Honor States Program, an initiative of the National Governors Association (NGA) Center for Best Practices, and was conducted jointly with the National Conference of State Legislators.

Purpose

The fourth trip in this project took participants to Raleigh, North Carolina, for an intensive look at the state’s high school reform strategies, particularly the creation of new high schools focused on Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) and efforts to create early college high schools, a five-year high school program that allows students to earn an associate’s degree or up to two-years of transferable college credit. The trip was designed to provide participants with an understanding of the state’s overall high school reform strategy, the key players at the state-level involved in its creation and evolution, and an appreciation for the lessons learned as the state has progressed.

Participants included state legislators, as well as state and district education leaders from Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Oklahoma, and Rhode Island.

Background—North Carolina’s Focus on High School Reform

North Carolina has been focused on reforming high schools for almost a decade. In 1999, the state convened a High School Roundtable, at which goals were identified, and state leaders began recruiting both foundation support and the assistance of national organizations to get a variety of initiatives underway.

North Carolina’s high school redesign approach has three main components:

- Redesigned High Schools / High School Innovation (STEM-focused new high schools and Early College High Schools)

- Advocacy and Citizen Engagement (a state-wide engagement campaign)

- Policy Solutions (default college-prep curriculum and infusion of 21st Century Skills, standards, and assessments into current state standards and curriculum)

Urgency for Change

There were a number of concerns that led state education leaders and the business and higher education communities to call for redesigned high schools. These concerns included: low graduation rates; inadequate preparation for postsecondary study among those who did graduate; and new demands for higher-level skills prompted by a changing economy. Between 2000 and 2005, the decline of North Carolina’s manufacturing industry led to a loss of 184,200 jobs—a 24% decline.

The need for dramatic changes in secondary education is a key focus of the Governor’s economic plan for North Carolina, and that focus has generated political momentum for high school reform. At the same time that the state faced a decline in manufacturing jobs, there has been an increase in jobs in biotechnology industries that require advanced degrees. Additionally, unsatisfactory academic achievement (reflected in an overall graduation rate of 60%, for example, with only 58% of African Americans and 53% of Hispanics graduating) and other concerns made it clear that secondary education needed to be a primary focus.

These concerns led leaders to focus on the need for both higher expectations for high school graduates and new strategies for secondary education. The urgency of the state’s need to improve its national and global economic competitiveness has meant an intense focus on STEM education. North Carolina is below the national average in the number of high school students taking upper-level science and mathematics courses—and girls and minorities are least likely to take high-level science and math courses. Thus, along with an overall focus on high school redesign, North Carolina has highlighted STEM education at the secondary level by making STEM-related fields the theme of many of the redesigned high schools and by developing a replication model for future efforts that blends project-based learning with a pre-engineering curriculum.

Structure for Statewide Leadership

Today, North Carolina has put into place a leadership structure to oversee high school reform, as well as a variety of targeted programs. Governor Michael Easley, supported by his working committee called the Education Cabinet (comprised of the General Assembly, the State Board of Education, and the Department of Public Instruction), has been working together to identify funding to support high school reform, to pass legislation that supports innovative high school models, and to coordinate policy and administer new programs.

In 2003, Governor Easley launched the North Carolina New Schools Project (NCNSP), funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, designed to bring dramatic structural change to the state’s high schools. NCNSP operates as a private-public partnership to focus leadership and financial resources directly to redesigning high schools. It began with the premise that reform takes place one school at a time, but that successful reform must be sustained, supported, and replicated. NCNSP’s goals are to change instruction; provide rigor for all students; and prepare all North Carolina graduates for college, work, and citizenship. NCNSP has collaborated with the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction on a STEM Advisory Team of business leaders, engineering professionals, higher education administrators, and others who provide guidance and advice regarding STEM education in the state.

Another related program started by the Governor’s Office is the development of Learn and Earn Early College High Schools, a collaborative effort between secondary and postsecondary education institutions that enable students to graduate in five years with a high school diploma and an associate’s degree or two years of transferable college credit. Without support and leadership from a number of other agencies, including the North Carolina Community College System, University of North Carolina System, North Carolina Independent Colleges & Universities, and the business community, this initiative would not be possible.

In addition, North Carolina is a member of the American Diploma Project, an effort to ensure students graduate from high school ready for college and work by raising the rigor of the high school standards, assessments, and curriculum and aligning those expectations with the demands of postsecondary education and work. In April 2005, North Carolina was also the first state in the nation to create a Center for 21st Century Skills in partnership with the national Partnership for 21st Century Skills. The Center, which is located in the North Carolina Business Committee for Education in the Governor’s Office, is focused on the redesign of high school curriculum, assessments, and teacher professional development. The Center’s framework emphasizes analytic thinking, problem solving, communication and collaboration, as well as critical subject matters such as global awareness, civic engagement and business, and financial and economic literacy.

In addition to its programmatic initiatives, NCNSP launched an Advocacy and Communications Initiative, designed to highlight the urgent need for reform across the state and to introduce the three key elements of the state’s approach: rigor, relevance, and relationships. To support this effort, NCNSP has also disseminated an Action Plan for High School Innovation to guide local districts and schools in undertaking reforms on their own. These initiatives are informed by the North Carolina Center for 21st Century Skills, through which educators, administrators, and business leaders work to identify the skills North Carolina students will need if the state is to continue to improve its economic standing.

Commitment to Innovative High School Redesign

In 2003, North Carolina enacted the Innovative Education Initiatives Act of 2003 (updated in 2005), which allowed policy waivers regarding seat time requirements and limited age restrictions for younger students enrolling in institutions of higher education, thus leading to the creation of innovative high school models including Learn and Earn high schools.

North Carolina is committed to statewide strategies to improve low-performing high schools and has made a significant commitment to this endeavor. Any school in which fewer than 60% of students score at the proficient level on the state’s end-of-course tests in academic subjects for at least two years in a row will be required to undergo restructuring and redesign. Under the Governor’s plan, schools may select among several models to guide their redesign, or the NCNSP can take over the process. In 2005, the State Board of Education sent “turnaround teams” into 44 failing schools.

Professional development for educators involved in redesign and improvement has been central to the state’s high school redesign plan. Over the summer, more than 400 teachers, counselors, and administrators from 52 schools redesigned or new Learn and Earn schools attended a professional development institute focused on leading innovative high schools. In addition, the state held a separate summer institute for teachers who would be working in one of the New Technology high schools being adopted in six schools across the state.

The state’s approach is to combine a steady increase in the number of schools that are successfully preparing students for college and work, particularly in STEM fields, with steady improvements in the systemic supports for innovation and excellence. In this way, they intend to gradually raise expectations for all students and all schools—making excellence and high achievement the norm in North Carolina high schools. Early results indicate that this level of commitment from the state is showing promise—attendance rates are up at many of the redesigned schools and disciplinary referrals are down. The redesigned high schools are new; however, the NCNSP will continue to monitor progress, especially academic achievement in the coming years.

Participants were able to see three of North Carolina’s redesigned high school models: a STEM academy, New Technology high school, and a Learn and Earn high school. In addition, they were given opportunities to hear from and interact with state leaders from the legislature and education community regarding the political climate necessary to create these changes. Participants use the information and contacts from this trip to inform work in their home states regarding high school design.

South Granville School of Health and Life Science

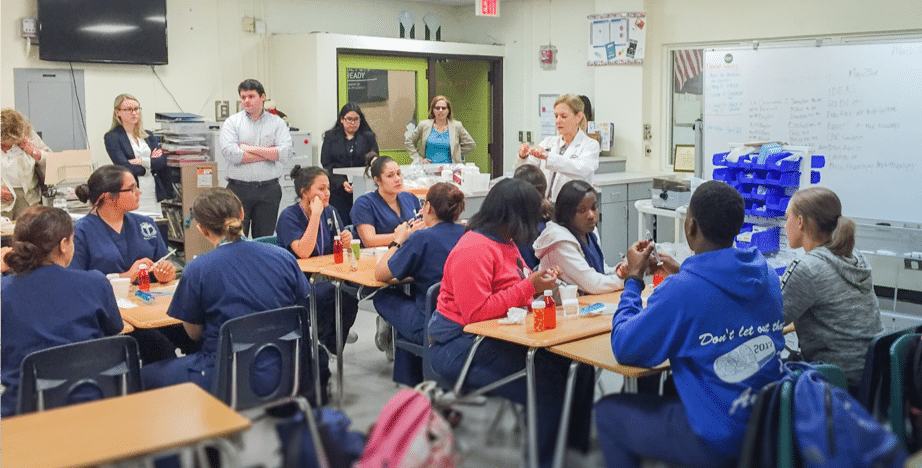

The first visit was to the South Granville School of Health and Life Science (SGHLS), a school with 227 students and the first of three autonomous, theme-based high schools to be located within the campus of the larger South Granville High School. SGHLS is one of six health and life science themed schools opened in North Carolina with support from the NCNSP. Participants had an opportunity to observe classrooms and meet with teacher and student panels.

SGHLS has a rigorous, college-preparatory curriculum drawing from the fields of biology, medicine, and nutrition. The goal is not to track students into particular careers, but to allow them to consider the real-world context of the material they cover. Typical course offerings might include medical sciences, sports medicine, early childhood education, animal science, computer applications, or business entrepreneurship.

The school has double class periods and a focus on project-based learning. Students are encouraged to participate in internships and job shadowing opportunities with professionals in the health care and other industries. Because of its size, SGHLS encourages the development of sustained relationships among students and faculty. The academic standards are high, but advisors support students throughout their four years, and all faculty are committed to providing the supports students need for success. Students indicated that the teachers play a critical role in their success. Moreover, smaller than usual class sizes (15 to 20, as opposed to the North Carolina norm for high school class size of 35) were also cited by students as important to their learning experience. As one student said, “the difference with this school is that it’s about what they expect of you. Here I have the one-on-one attention that I most need.”

Students must apply to the school through a process that includes an interview and review of students’ grades and activities, and not all are admitted. Students commented that the decision to attend meant leaving their friends, but that the education and new relationships they are forging were worth it.

From the teachers’ perspectives, the relationships with students have improved because the small school size allows teachers to build one-on-one relationships with students. They eat lunch with students, and have more time in general to get to know them than they would at a regular high school. Perhaps most important to the teachers is the way their time is structured. Teachers have time set aside for collaboration through common planning time. Their classes have mixed ability levels, but teachers said they were able to tailor their lessons to individual students’ needs, owing to three factors: planning time built in to the schedule, somewhat smaller class sizes, and computer-based testing programs used as needed to provide immediate feedback. The teachers explained that that they are able to leverage what they know about students to push them academically.

Participants noted that the comments from the staff and students showed a positive response to new policy initiatives and structural changes in the redesigned schools and research-based structural changes (small classes, focused curriculum, etc.) that supported improved student achievement and staff professionalism. Through their well-articulated answers and maturity, students on the student panel demonstrated the role of the school in supporting their growth and development as citizens of the world and future college students.

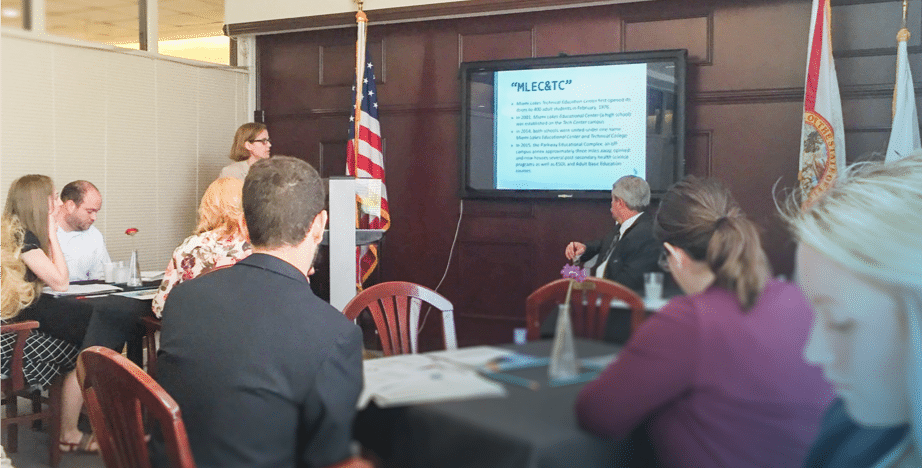

Partnering for High School Reform Session

Participants spent an afternoon at the offices of the North Carolina New Schools Project (NCNSP) and had the opportunity to hear from policy leaders and elected officials about innovative high school reform strategies, ways of building consensus around these strategies, and the opportunities they see to build on what North Carolina has already accomplished.

The first presentation provided background on North Carolina’s high school redesign effort and NCNSP’s role in it. Deputy State Superintendent Janice Davis noted that North Carolina is a state-controlled system, in that the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction provides funding for public education and mandates curriculum statewide. Quality control happens at the state-level through rules, regulations, and guidelines, but this can serve as a barrier to innovation. However, the 2003 Innovative Education Initiative Act was an opportunity to move past that barrier by allowing the state to step aside to allow for innovation. The law enabled flexibility in funding (such as principal salaries no longer are based upon school size), autonomy for small schools where they are accountable for their own AYP results, and lifting seat-time requirements to allow students to concurrently enroll in postsecondary institutions. Davis added that the process for obtaining waivers is quite difficult, which is something the state is hoping to rectify.

According to Tony Habit, President of the NCNSP, “successfully redesigned individual schools are not enough—for the redesign effort to take hold these schools must be linked to a system that works with them, and they must be the inspiration for innovation in other schools.”

The first step has been to put in place small high schools related to growing economic sectors within the state, specifically health and life sciences, engineering, and computer technology. But the hardest part of reform is not changing the school structure, according to Tony Habit, it is changing adults’ perceptions and expectations. “We are struggling against belief systems such as ‘fix the kids, not the schools’ and expectations that go along with poverty. We have to gradually unpack these beliefs and make the work personal for teachers, administrators, and all others who are involved in educating children.”

Davis and Habit noted that a key goal in supporting innovative reform was to counteract pessimism about how much improvement is really possible for disadvantaged students in high-poverty settings. Davis and Habit stressed that both the Education Cabinet and the NCNSP have made sustainability and systemic reform key priorities.

Participants questioned whether the work would be sustainable in the long-term. They also wondered about the state’s approach of using policy changes as a catalyst for changing teacher and administrator beliefs would catalyze the type of change the state is moving toward. The presenters were candid and open about the challenges that North Carolina faces with using policy as a primary lever for changes in teacher buy-in and classroom teaching. The state is working to make their efforts sustainable and, since much of the work was still new, they encouraged participants to continue to share information about their states’ work and continue to check in with state leaders in North Carolina when results become available in the coming years. Davis indicated, “I continue to be surprise by what I’m learning and how its influences the directions of our reform efforts.”

Brokering Policy Change through Legislation

The second presentation of the session gave participants an understanding of the political climate in North Carolina that enabled the passage of the Education Initiatives Act. In addition, key representatives from statewide education agency talked about their role in continuing to facilitate a climate of collaboration. The presenters pointed to the Learn and Earn high schools as an example of a reform strategy facilitated by legislative change, but executed through partnerships between statewide education agencies.

Through North Carolina’s Learn and Earn high schools, students are encouraged to draw on options available at nearby community colleges. They attend high school for five years and graduate with both a high school diploma and either an associate’s degree or two years of transferable college credit. The goals are to encourage students who might not otherwise consider college to begin planning for the future early, and to help make postsecondary study both affordable and accessible to all students. “This allows some time for youngsters to develop a life plan, but set aside money for higher education, a distributive education concept,” said Howard Lee, Chair of State Board of Education.

Dr. Ken Whitehurst, Associate Vice-President of the North Carolina Community College System, explained, “North Carolina has 58 community colleges—one within a 30-minute drive of every resident—so participation by the community college system was imperative to making this option widely available to North Carolina youth.” In 1997, the state developed a comprehensive articulation agreement allowing students who earn an associate’s degree at any community college in the state to enter a four-year North Carolina institution with two years of transferable credit. Moreover, “Learn and Earn high schools are funded as traditional high schools, so students pay nothing for college courses taken through them,” explained Don Yongue, Chair of the North Carolina House Education and Oversight Committee.

Ann McArthur, Teacher Advisor to Governor Easley, discussed the Teacher Working Condition Survey, which is used in every school throughout the state to gauge teachers’ job satisfaction. According to the latest survey, 46% of teachers in redesigned high schools “strongly agree” that their school is a “good place to teach and learn,” as opposed to only 26% in other high schools. In addition, teachers in redesigned schools reported, on average, higher levels of satisfaction in all categories: leadership, professional development, facilities, use of time, and teacher empowerment.

The presenters stressed that collaboration between the legislature, higher education system, and the K-12 education system have been key, not just to the successful launch of the Learn and Earn schools, but to many aspects of reform in the state.

Participants questioned the presenters on the financing reform efforts like Learn and Earn high schools. Unfortunately, the presenters could not speak to the details, but they indicated that the infusion of funds from the state set aside in the Education Initiatives Act had played a large role in bringing the key players to the table. The presenters also believe the state will continue to support these efforts through financial contributions ensuring their sustainability.

Purnell Swett Information Technology High School

The second day of the trip began with a visit to Purnell Swett Information Technology High School, one of North Carolina’s newest schools , which opened in the fall of 2006. Purnell Swett is located in the southeastern, rural part of the state near the town of Pembroke. This small school of approximately 100 students in Grades 9 and 10 serves a disadvantaged population (73% of its students qualify for free or reduced price lunch) using an academically rigorous curriculum and state-of-the-art technology. Purnell Swett is one of several Information Technology high schools in the state, all of which are designed to integrate technology into all aspects of the curriculum, and use it to support both research and practical applications.

The program is based on a model developed by the New Technology Foundation, which was first developed in California and is being replicated around the country. The model is a method of instruction—as opposed to prescriptive curriculum—designed to prepare students to excel in both in college and in an information-based, technologically advanced work environment. Students use technology in a variety of ways and technology also supports specific educational strategies such as the development of a digital portfolio and assessment tools customized to particular learning outcomes.

The Purnell Swett program is small and has small class sizes (average is 25 students), but it is integrated with the local comprehensive high school as it is located in one corridor of the building. Although the goal is for it to become entirely autonomous, the current arrangement allows students to take electives at the larger school, which, in turn, allows common planning time for teachers. This planning time is important both as an opportunity to build on the targeted, week-long professional development that took place before school started in the fall, and also to facilitate the interdisciplinary approach that is a key element of the program. Project-based learning is the principal instructional strategy and is closely aligned with the skills identified through the 21st Century Skills Partnership. Projects are managed by groups of students who sign contracts spelling out their responsibilities—and who have considerable control over the process (e.g. they can “fire” a student who is not contributing). Computers are heavily used, and the school is close to having one computer for each student, since many may not have them at home.

So far, the principal and teachers cite few problems. Perhaps, most significant is the need to build students’ reading and writing skills as many students reach ninth grade without the literacy skills to work independently at grade level. Participants commented on the faculty’s commitment to teaching kids to learn as teachers, themselves, were also learning how to use new technology and aligned it with North Carolina’s state standards.

Robeson Early College High School

The final visit was to one of North Carolina’s Learn and Earn High School campuses, the Robeson Early College High School (RECHS). Wesley Revels, Principal, explained the systems of academic support, as well as school-to-work opportunities and counseling available to students. “The resources here help students meet these expectations and navigate the college environment so that they are prepared to pursue further postsecondary study after graduation,” said Revels. North Carolina’s goals for the program include clear links between the curriculum and the world of work, redesign of grades 9 and 10 to prepare students to meet college-level expectations in their junior and senior years of high school, and partnerships with middle schools to raise awareness and preparedness for ninth grade.

RECHS, which is located on the campus of Robeson Community College, has 142 students in grades 9 through 12. The students all must meet the same entry requirements that entering students at Robeson Community College must meet in order to attend college classes, and only students who are “seriously focused on attending college” are encouraged to apply. However, students are supported throughout the program through collaboration among faculty at the high school and the college, overseen by a college liaison. The high school students also participate in job shadowing and internship programs, overseen by a school-to-work coordinator.

Dr. Charles Chrestman, President, Robeson Community College, said that RECHS students are fully integrated into the Robeson Community College (RCC). They have the same ID cards as students who are traditionally enrolled, have access to computer labs and library services, and are doing as well as traditional students in their classes. Dr. Chrestman stressed that he and his faculty believe strongly in the program and would like to see it expand. “We believe it is our mission to serve the kids, which is why there is no resistance from us. The students, teachers, and administration have our full support and we consider ourselves to be partners in this effort,” said Chrestman.

Some students have found RECHS to be very different from their home schools. Although they missed the social niches they had developed, they are enjoying the opportunities afforded to them by being on a community college campus. These students will be in high school for five years, and their daily schedule is different from that of other high school students to accommodate their enrolment in college-level classes. Moreover, RECHS does not offer sports, though some other extracurricular activities are being developed and students may also participate in activities at Robeson Community College.

Takeaways: Lessons Learned

- North Carolina has created a formal structure that involved all key stakeholders for state-wide leadership. The Education Cabinet involves all the key stakeholders: governor’s office, legislature, secondary and postsecondary education systems, and key business and community leaders. This formal structure helps to support and drive the state’s education decision making.

- North Carolina’s high school redesign approach is systemic with an emphasis on sustainability. Leaders have leveraged private support with public funds to ensure the longevity of these initiatives. In addition, North Carolina has engaged in building public support for this work through public advocacy campaigns. With the large infusion of private resources, one challenge for the state will be to make the reform efforts sustainable after the foundation funding subsides.

- Centralized state education system provides the context for reform. North Carolina did not have to deal with districts fighting to exert local control as most functions have been controlled by the state: salaries, standards and curriculum, and funding.

- With a centralized system, North Carolina has given autonomy to schools and programs to create educational experiences to best serve their students. The state framework provides a variety of models as best practices, yet allows for flexibility for schools to customize the model to the needs of their students based upon individual AYP results.

- North Carolina’s biggest challenge has been reaching the core: affecting the teaching and learning at the classroom level. Teachers often have a romantic attachment to the past and see the structure change around them, but do not change their practice. Many have the attitude that they are masters at their craft and are yet unmoved about the need for changed instruction.

Contacts

Dana Babbitt

Superintendent

South St. Paul Public Schools

104 5th Avenue South

South St. Paul, MN 55075

651-457-9465

dbabbitt@sspps.org

Jim Ballard

Executive Director

MI Association of Secondary School Principals

1001 Centennial Way, Suite 100

Lansing, MI 48917

517-327-5315

jimb@michiganprincipals.org

Patricia Bernhoft

High School Specialist

Minnesota Department of Education

1500 Hwy 36 W

Roseville, MN 55113

651-582-8754

pat.bernhoft@state.mn.us

Iris Bond Gill

Senior Program Associate

American Youth Policy Forum

1836 Jefferson Place, NW

Washington, DC 20036

202 775-9731

ibgill@aypf.org

Catherine Brooks

Principal

South Granville High School of Health Sciences

701 N. Crescent Drive

Creedmor, NC 27522

919-693-5510

brooksc@gcs.k12.nc.us

Jennifer Brown Lerner

Program Associate

American Youth Policy Forum

1836 Jefferson Place, NW

Washington, DC 20036

Business: 202-775-9731

jlerner@aypf.org

Mark Buesgens

Chairman

Education Policy and Reform Committee

Minnesota House of Representatives

4500 Golfview Drive

Jordan, MN 55352

651-296-5185

rep.mark.buesgens@house.mn.us

Harold Carver

Principal

South Granville High School

701 N. Crescent Drive

Creedmor, NC 27522

919-693-5510

carverh@gcs.k12.nc.us

Janice Davis

Deputy State Superintendent of Public Instruction

North Carolina Department of Education

6301 Main Service Center

Raleigh, NC 27699-6301

919-807-3441

jdavis@dpi.state.nc.us

Sophie Frankowski

Director

North Carolina New Schools Project

4600 Marriott Drive, Suite 510

Raleigh, NC 27612

919-277-3765

sfrankowski@newschoolsproject.org

Joseph Garcia

Vice President

Advocacy and Communications

North Carolina New Schools Project

4600 Marriott Drive, Suite. 510

Raleigh, NC 27612

919-227-3777

jgarcia@newschoolsproject.org

Heather Grinager

Senior Policy Specialist

National Conference of State Legislatures

7700 East First Place

Denver, CO 80230

303-856-1392

heather.grinager@ncsl.org

Chris Hayter

Program Director, Economic Development

Social, Economic, & Workforce Programs Division

National Governors Association

444 N. Capitol St. Suite 267

Washington, DC 20001-1512

202-624-5300

chayter@nga.org

Jim Hofer

Principal

Staples Motley High School

202 Pleasant Ave. NE

Staples, MN 56479

Business: 218-894-2431 / Fax: 218-894-1828

jhofer@isd2170.k12.mn.us

Nancy King

Maryland State Delegate

Maryland State Legislature

9901 Shrewsbury Court

Montgomery Village, MD 20886

301-963-0034

nik107@aol.com

Sharon Lee

Fellow, Office of Middle and High School Reform

Rhode Island Department of Education

255 Westminster Street

Providence, RI 02903

401-222-8484

sharon.lee@ride.ri.gov

Alan Mabe

Vice President

Academic Planning and University Programs

University of North Carolina- Chapel Hill

910 Raleigh Road, P.O. Box 2688

Chapel Hill, NC 27515-2688

919-962-4589

mabe@northcarolina.edu

Ann McArthur

Teacher Advisor to Governor

Office of Governor Mike Easley

20301 Mail Service Center

Raleigh, NC 27699

919-733-3921

ann.mcarthur@ncmail.net

Paul McKinley

Co-Chairman

Senate Education Committee

Iowa State Senate

21884- 483rd Lane

Chariton, IA 50049

bmcneal@ncasa.net

Bill McNeal

Executive Director

North Carolina Assoc of School Administrators

P.O. Box 27711

Raleigh, NC 27601

919-828-1426

Claire Noble

Deputy Director of Government Relations

Minnesota Department of Education

1500 Hwy 36 West

Roseville, MN 55113

651-582-8742

claire.noble@state.mn.us

Delores Parker

Vice President for Academic and Student Affairs

North Carolina Community College System

5616 Mail Service Center

Raleigh, NC 27699-5016

919-807-7069

parkerd@nccommunitycolleges.edu

Toni Patterson

Consultant

North Carolina New Schools Project

4600 Marriott Drive, Suite 510

Raleigh, NC 27612

919-227-3762

tpatterson@newschoolproject.org

Jim Reynolds

State Senator

Oklahoma State Senate

2300 N. Lincoln Blvd. ,Rm. 534B

Oklahoma City, OK 73105

405-521-5522

reynolds@oksenate.gov

Mark Schmitz

Superintendent

Staples-Motley School District

202 Pleasant Ave. NE

Staples, MN 56479

218-894-2430

mschmitz@isd2170.k12.mn.us

Linda Suggs

Program Officer

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

105 Pember Place

Morrisville, NC 27560

919-280-2233

Charlie Toulmin

Senior Policy Analyst

Education Division

National Governors Association

Center for Best Practices

444 North Capitol Street, Suite 267

Washington, DC 20001-1517

202-624-7879

ctoulmin@nga.org

Nancy Walters

Program Manager

Minnesota Office of Higher Education

1450 Energy Park Drive

St. Paul, MN 55108-5227

651-642-0596

nancy.walters@state.mn.us

Ken Whitehurst

Associate Vice President, Academic & Student Svcs.

North Carolina Community College System

5016 Mail Service Center

Raleigh, NC 27699

919-807-7100 x414

whitehurstk@nccommunitycolleges.edu

Tom Williams

Superintendent

Granville County Schools

101 Delacroix Street

Oxford, NC 27565

919-693-4613

Don Wotruba

Director of Legislative Affairs

Michigan Association of School Boards

1001 Centennial Way, Suite. 480

Lansing, MI 48917

517-327-5913

dwotruba@masb.org

Doug Yongue

State Representative

North Carolina House of Representatives

1303 Legislative Building

Raleigh, NC 27601-1096

Business: 919-733-5821

douglasy@ncleg.net