Maria Duarte, AYPF Policy Associate;

Nicole Chandonnet, 2020 AYPF Intern

The Impact

To date, the United States has over 2.5 million reported COVID-19 cases and more than 128,000 deaths. Regrettably, these startling numbers do not seem to be slowing down as states like California, Florida, and Texas have seen a surge in COVID-19 cases given their reopening plans. The impact of COVID-19 in America is undeniable; what is also undeniable is the fact that COVID-19 has amplified – not introduced – many systemic inequalities hindering Black and Brown communities, youths, and families from having a fair shot at success.

Unfortunately, COVID-19’s impact trend is painfully familiar to the American people. Non-white communities, particularly Black and Latinx communities, are suffering at higher rates and are disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. Compared to their population share, Black individuals are dying at a rate more than 1.5 times higher; Latinx and Hispanic folks are testing 2.5 times higher in 30 states and over 4 times higher in eight states. Furthermore, our most vulnerable young people, including those in contact with the foster care and juvenile justice systems, have reported a loss of employment, lack of access to healthcare and mental health services, and increasingly experience intensified housing and food insecurity amongst other challenges.

The rapid spread of the coronavirus resulted in extensive health-related preventative measures including social distancing, national school closures, reduced mental and healthcare services, and closure of non-essential businesses, including service-sector jobs. Although preventative measures are necessary for safety to control the spread of the virus, we must grapple with the harsh reality that many preventative measures further exacerbate challenges experienced by our most vulnerable youth: foster youth and justice-involved youth.

(Source: COVID Tracking Project and the Boston University Center for Antiracist Research)

Walking in Their Shoes

Since the aftermath of the Great Recession in 2010, strides have been made towards engaging disconnected youth.[1] In 2018, 11.2%, or 1 in 9 young people were considered disconnected youth – down from 14.7% (or 1 in 7 young people). Regrettably, COVID-19 poses a threat to these gains as experts warn the pandemic will bring the total number of disconnected young people to about six million, or about 1 in 4.

Young people across the country are already experiencing intensified challenges due to the pandemic. In a recent AYPF conversation with foster youth and justice-involved youth, Mallory, a former foster youth residing in New York City, drew parallels between the pandemic and her reality:

“I never had control of my life growing up, and the pandemic has reintroduced a lack of control. We do not have control over whether we are going to lose our jobs or what is going to happen in our lives.”

In other instances, justice-involved youth from Philadelphia shared their concerns regarding income and the consequences of employment disruption:

“Trying to pay bills is killing me. I don’t have parental support; I’m on my own.” – Brittany

“I fear [it] not being over soon; not being able to work. I am still on my own and it’s hard to pay rent.” – Shanice

Too often, our most vulnerable young people are left with the arduous task of navigating systems, institutions, and spaces that were not built or designed with them in mind. At best, these systems prove to be ineffective at increasing young people’s success. At worst, they actively perpetuate harmful and racist ideologies about foster youth and justice-involved youth, further widening educational and economic gaps. Rashawn, a justice-involved male from Philadelphia, shared one of his biggest fears during COVID-19: “My fear is the system…catching cases. It is hard for a young man. I’m 22 and on my own with my girlfriend. It’s hard when you have a case and you can’t get a job. They look at you like you’re a criminal.”

What does it tell us about the systems whose main function is to “support” our most vulnerable young people, if those very systems are what young people fear the most during a crisis? Who will they turn to?

Financial Hardships / Employment Challenges

Steady employment is necessary to achieve financial security, which forms the foundation of a healthy, sustainable life. In the middle of March, many individuals found these safety nets pulled from underneath them. Foster youth and justice-involved youth proved to be no exception.

FosterClub, a national network for young people involved in foster care, conducted a survey to assess the impact of COVID-19. They found that 65 percent of transition-age foster youth who were employed before the pandemic lost their jobs by May. Moreover, half of the individuals who applied for unemployment benefits did not receive assistance. Many foster youths rely not just on a single job but work multiple jobs to ensure financial stability and security. Despite their best efforts, by mid-March, thousands of individuals found themselves without employment or resources to assist them.

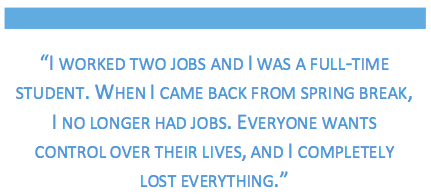

Resident of Orlando, FL, and former foster youth, Daftne, remarked, “I worked two jobs and I was a full-time student. When I came back from spring break, I no longer had jobs. Everyone wants control over their lives, and I completely lost everything.” Even though she eventually got one of her jobs back, she reported that it was not enough to financially support herself.

Resident of Orlando, FL, and former foster youth, Daftne, remarked, “I worked two jobs and I was a full-time student. When I came back from spring break, I no longer had jobs. Everyone wants control over their lives, and I completely lost everything.” Even though she eventually got one of her jobs back, she reported that it was not enough to financially support herself.

In March and April, the Department of Child and Family Services (DCFS) in California, Illinois, and Ohio extended funding for individuals aging out of the foster care system, so that they would continue to receive financial and housing assistance. While this has provided much- needed relief for many foster-youth, Leigh-Anna aged out of the system in California in February. Shortly afterwards, she lost her job and housing due to challenges presented by COVID-19. Leigh-Anna wishes that some of the benefits given to those aging out of the system in March were applied retroactively, as she did not receive any additional support.

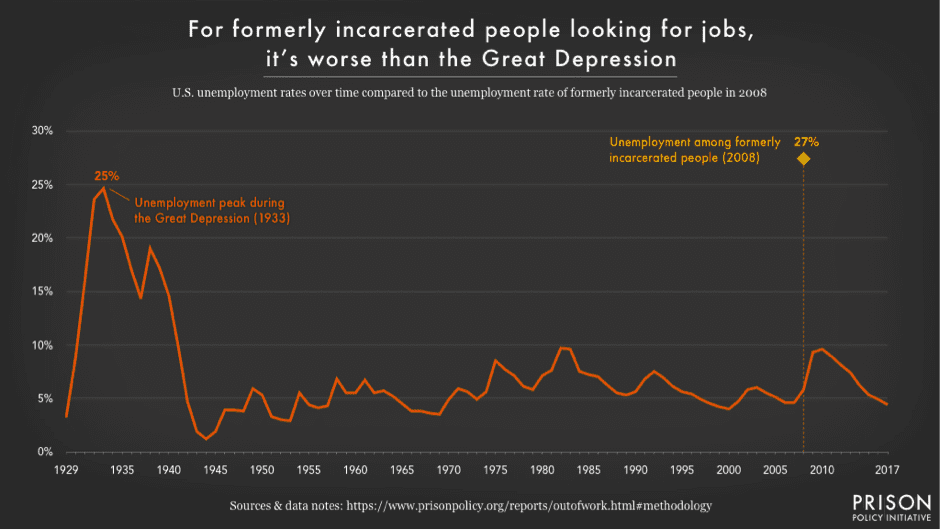

The situation looks similarly bleak for justice-involved youth. Prior to the pandemic, the unemployment rate for formerly-incarcerated individuals was over 27 percent, with the rate disproportionately higher for Black men and Black women at 35.2 and 43.6 percent, respectively.

With the closure of non-essential businesses and many service jobs, thousands of individuals found themselves out of work. Justice-involved youth Marquez worked at a nightclub in Orlando, FL, and he lost his job when they closed in mid-March. He noted, “I was constantly looking for other jobs, but it was difficult to find anything with full-time hours.” He also expressed frustrations with the process of filing for unemployment as it was complex and required many additional resources. While providing unemployment benefits to individuals in need is necessary to counteract the financial shocks of the pandemic, government officials and social-service workers alike must ensure that they provide people with assistance and tools to effectively use these resources, otherwise their efforts will be in vain.

The loss of jobs and financial insecurity that many young people found themselves facing in the middle of March bred mental health challenges as many were not only without a job, but also physically isolated from friends and family– not to mention, dealing with intense anxiety over contracting COVID-19.

Mental Health Challenges

It’s been long known that youth with mental and behavioral health disorders are overrepresented in the juvenile justice system. Studies suggest that in some instances as many as 70 percent of justice-involved youth have an undiagnosed mental health disorder. Similarly, a staggering 80 percent of foster youth suffer from a mental health issue. The impact of COVID-19 on young people has further exacerbated these challenges.

Their lack of trust of adults, limited positive role models, coupled with young people’s sense of isolation puts them at higher risk of being stressed, especially during a pandemic. The often unclear guidance from state and federal leaders, combined with rapidly-changing CDC guidelines, makes it difficult for young people to feel a sense of security. As Daftne shared, “…how quickly we react to things can greatly influence your mental state. It is hard to get to resources I and my loved ones need, and that has been isolating.” Socially distancing has also taken a toll on young people:

“… It’s hard on my mental health, when there’s nothing to do. I stopped taking my medication, which generally helps to regulate my emotions. It was a really hard time to find things to keep busy. It’s hard when it’s basically against the law to have human contact.” -Taylor, former foster youth, Rhode Island

Additionally, young people have also experienced emotional stress from the sudden closure of college campuses nationwide. Many colleges and universities pressured students to return home when the pandemic first erupted due to health concerns. For many vulnerable groups, such as first-generation college students and students experiencing homelessness, returning home is not always positive. For Leigh-Anna, a New York college student who was forced to return home to California, it’s been a challenge:

“…I have to live with my family members who are [ignorant] and struggle with addiction issues, which makes conversations difficult.”

Like for Leigh-Anna, displacement from college campuses for many students results in a return to toxic and often dangerous home environments; for others, a home away from college is nonexistent.

Socially distancing and evacuating college campuses are two appropriate responses to curb the spread of the virus. At the same time, Daftne and Leigh-Anna’s stories remind us of the challenges to ensure every young person has access to a healthy support system during a crisis.

Women as Caregivers/ Parenting

The pandemic introduced a lack of autonomy with which foster youth and justice youth are far too familiar. These challenges necessitate relying on other people for financial and emotional support. However, many foster youth and formerly incarcerated youth do not have access to such support networks.

Only thirty-seven percent of transition-aged foster youth have family members (legal or chosen) that they can rely on during the crisis. Twenty percent reported that they are entirely on their own. Former foster youth and resident of Ellsberg, Washington, Autumn, is the sole caretaker of her younger brother and sister. She expressed anxiety about getting COVID-19: “I am fearful of catching the virus and dying and leaving [them] with no one. I have had to write a will and figure out who will take care of my siblings if something happens to me.”

These issues do not occur in isolation, but rather compound one another. Marcia, a formerly incarcerated youth, contracted COVID-19 in New York City, and she was sent home because there was no space for her in the hospital. While she financially supported herself without either the stimulus check from the government or familial support, she is uncertain that she will be able to continue to do so if there is a second wave of the virus.

Moreover, the United States is home to nearly five million young parents between the ages of 16 and 24. 58 percent of these parents were single when they had their child, and they are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of COVID-19, as they are frequently low-income and have a high-risk of experiencing education and employment disruptions.

Recent high school graduate and former foster youth Jaylynn works multiple jobs to be reunited with her daughter. Not only does she have to support herself with little assistance from the DCFS, she also wants to provide her daughter with a better future. Currently, she is relying on her boyfriend for housing, and she noted, “I would be homeless without his support.”

Often, in circumstances beyond their control, foster youth and justice-involved youth are forced to grow up far too quickly and interact with systems that they feel do not to look out for their best interests. The unique responsibilities for young women as mothers and caregivers present even greater challenges that policymakers must be aware of in confronting the realities of COVID-19.

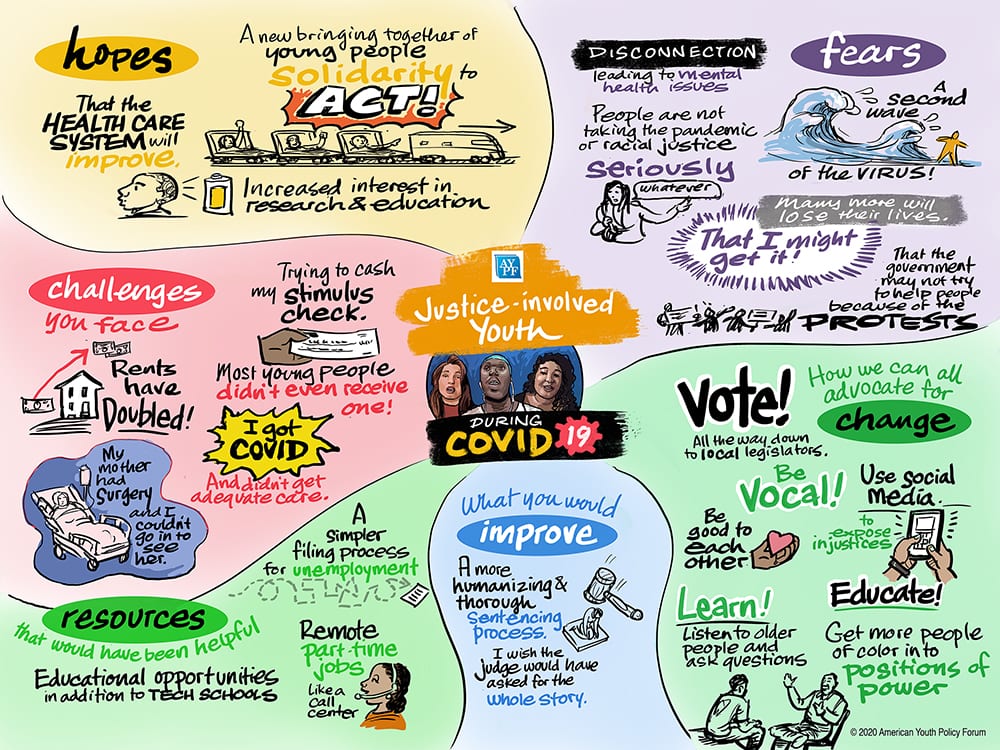

(Key-takeaways from our conversations with foster youth and justice-involved youth on the impact of COVID-19 on June 17, and June 24, 2020, respectively – click on the above images for hi-resolution versions.)

A Beacon of Hope

The disproportionate impact of the coronavirus, in addition to other recent events including national protests calling for justice in the brutal deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, has rightfully sparked social unrest. What’s been particularly encouraging to witness among all the tragedy is the resilience and determination of young people – who are in many ways leading the fight towards social justice.

Young people seek, and should be given, an opportunity for more meaningful involvement in advocacy and policy change initiatives. Fortunately, young people are increasingly being hired at non-profits, government agencies, and in some cases, represented in boards including city council and school boards. When young people are given governing power, it reinforces the idea that they have something meaningful to contribute to their respective communities, in turn boosting their confidence and sense of belonging.

Young people understand the immense opportunity we have in this current moment to dream bold and big — towards a more equitable and just society. Neha, a justice-involved youth residing in Ohio, expressed that she hopes this moment brings “solidarity…people coming together to act.” Young people also understand the value of educating themselves on prominent issues. Marquez, a justice-involved youth, shared he’s hopeful for “increased interest in research and education on governmental, political, and historical issues. [I] believe in the power of learning from history and finding facts amidst false media.”

We must lean on the expertise and knowledge of those hardest hit by COVID-19 during this moment of uncertainty and divisiveness. We must expand the definition of ‘expert’ beyond a college degree — recognizing the value of lived experiences, which often equip young people with solutions to the most critical social issues of our time. Kat, a former foster youth from Vermont, shared how we have fallen short of delivering on this promise: “We’re told we’re the experts; but when we apply, they note they want people with degrees.” May each of us strive each day to make Kat’s experience less common and commit to making room for young people at the table.

We must lean on the expertise and knowledge of those hardest hit by COVID-19 during this moment of uncertainty and divisiveness. We must expand the definition of ‘expert’ beyond a college degree — recognizing the value of lived experiences, which often equip young people with solutions to the most critical social issues of our time. Kat, a former foster youth from Vermont, shared how we have fallen short of delivering on this promise: “We’re told we’re the experts; but when we apply, they note they want people with degrees.” May each of us strive each day to make Kat’s experience less common and commit to making room for young people at the table.

[1] Teens and young adults ages 16-24 who are neither attending school nor working.