One of the nation’s most popular approaches to high school reform, the Career Academies model, combines an academic course of study with job-related training, internships, and mentoring, in an effort to help students make a successful transition to postsecondary education and the world of work. Currently operating in close to 2,500 sites across the country, Career Academies have been an important part of the educational landscape for more than three decades, offering an alternative approach to the traditional comprehensive high school.

At this forum a major new report on Career Academies conducted by MDRC, a nonprofit, nonpartisan research firm was released. The 15-year evaluation, funded by the U.S. Departments of Education and Labor and a number of private foundations, assesses the long-term impact of Career Academies on participants’ educational achievement, employment status, income, and other factors. Using a random assignment research design, the study followed roughly 1,700 Academy students from the 8th through the 12th grade and eight years beyond, tracking their progress relative to a control group of students who applied to but did not participate in Career Academies. Overall, the study found Career Academies had a significant and positive impact on annual earnings, job security, and family stability, and no adverse effect on academic achievement and college attendance. The presenters discussed the effectiveness and policy implications of this research and the Career Academies approach.

James Kemple, MDRC’s Director of K-12 Education Policy, began by describing the context in which MDRC’s findings can best be understood. Over the past 5-7 years, he explained, the participation of teenagers and young adults in the labor market has declined significantly across the country, wages have been stagnant, and the period of transition from childhood to economic self-sufficiency has lengthened. Researchers have found that such transitions into the labor force tend to be more smooth for young people who leave high school with job-related experience and skills. Yet, in recent years, federal policymakers have shown little interest in integrating workforce preparation into the secondary school curriculum. Rather, emphasis has shifted to the goal of preparing all kids for college, and career and technical education (CTE) has been pushed to the side.

MDRC’s findings suggest that the Career Academies model—and CTE in general—deserves a closer look.

Specifically, the study found that eight years after their scheduled high school graduation, the young people who had participated in Career Academies averaged 11% (or $2,088) more in annual earnings than did members of the control group, amounting to $16,704 of additional income over eight years. The benefits were most dramatic for males, whose annual earnings outpaced their control group by 17% ($3,731), totaling almost $30,000 over eight years. Further, Career Academies had a positive impact on family formation—eight years after high school, those who had participated were significantly more likely to be living independently with children and a spouse or partner. Moreover, while critics long have argued that high school CTE programs might detract from academic performance, MDRC found no such adverse impact: Career Academy participants and the control group had similar academic records, graduation rates, and postsecondary attendance, and their performance was on par with or better than that of national samples of students from similar backgrounds who did not participate in CTE courses.

Additional research will be needed in order to explain why participation in Career Academies had a much greater impact on earnings for males than for females, why it had such a positive impact on family formation, and why it had little or no impact on academic achievement. Also, follow-up research is already underway to measure the fidelity with which the Career Academies model is being implemented across the country and to learn how that relates to overall program effectiveness.

While MDRC’s research will continue, the evidence is strong already as to the effectiveness of the Career Academy model. Investments in such high school CTE programs have considerable payoffs for students who participate, he concluded, and the program does not compromise their academic performance or plans for postsecondary education.

Charles Dayton, Coordinator of Public Programs at UC Berkeley, began by describing his nearly thirty years’ experience with the Career Academy model in California. Early evaluations of Career Academies were positive enough to persuade the California legislature to provide funding sufficient for dozens of sites across the state and to pay for the creation of program guides, workbooks, and other supporting materials. However, the MDRC study represents the first time that Career Academies have been subject to a rigorous national evaluation, and it is “extremely heartening”, said Dayton, “to see that the data confirms and extends earlier findings.”

The previous studies in California found that Career Academies had a positive impact on student attendance, grades, graduation rates, and college-going, while conferring all the benefits of the academic curriculum as well as providing workforce training. However, said Dayton, the early evaluations in California never had sufficient resources to do significant follow-up research or to perform the sort of randomized control-group study that MDRC has conducted. Of particular importance, he adds, is that the MDRC research has been able to show precisely how much and what sort of impact Career Academies have had over and above the effect of students’ self-selection into the program.

The policy implications of the research could be dramatic, Dayton continued. Since passage of the Smith-Hughes Act in 1917, the federal government has supported high school students in pursuing either career preparation or college preparatory studies. Only since 1990, though, have federal regulations allowed for funds to be put toward the integration of academic and career preparation. As the MDRC study reiterates, there is no reason for an either/or dichotomy; high school can and should prepare students for college and career.

The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) ought to be redesigned with this lesson in mind, Dayton concluded. While the law has served useful purposes, especially its emphasis on diagnostic evaluation, it has neglected to require the measurement of career-related skills or other outcomes of schooling. As the MDRC research makes clear, it is possible to measure such outcomes, and the law should require it, said Dayton.

JD Hoye, President of the National Academy Foundation (NAF), noted that she, too, has been working for roughly thirty years to improve educational and career opportunities for youth in economically depressed communities. In the 1990s she was active in the federal School-to-Work program, and her current job puts her on a parallel course, assisting Career Academies by securing the support and involvement of their local business leaders.

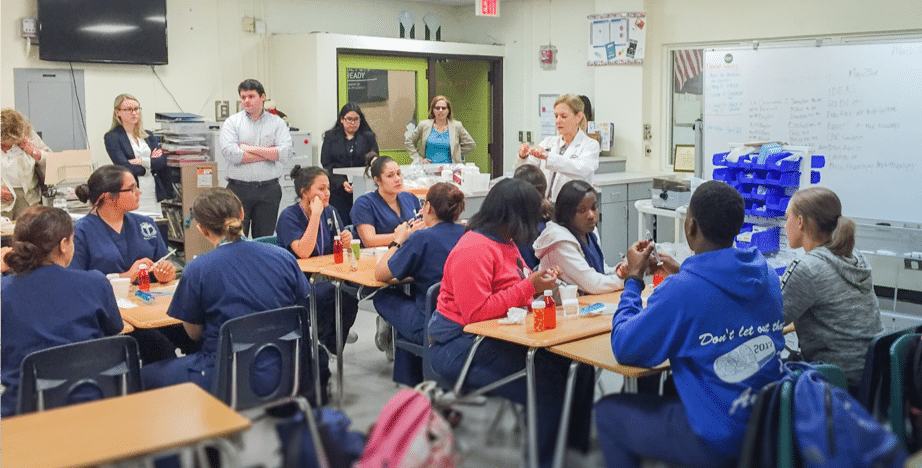

Specifically, said Hoye, NAF works with the corporate sector to identify labor market trends and to ensure that the high school curriculum takes into account the various kinds of jobs that are available in the region and the specific skills they require. Additionally, NAF helps schools set up student internships and mentoring opportunities with local employers. And it encourages corporate leaders to take an active role, beyond merely funding programs, in helping to improve their local high schools.

The value of this sort of corporate participation should not be underestimated, Hoye argued. As the MDRC study shows, Career Academies can have a powerful impact on students. However, if such programs are to be affordable, and if they are to remain effective, they will have to continue to build and maintain strong public/private partnerships.

Megan O’Reilly, Labor Policy Advisor to Rep. George Miller (chairman of the House Education and Labor Committee), offered a brief response to the presenters. She reiterated that in today’s economy, youth are most at risk of unemployment. It is essential that they receive early exposure to the labor market and that they develop marketable skills, so that they can make the transition to independence. Further, schools must not overlook the development of “soft skills,” such as interviewing, resume writing, and the like. For policymakers, the sort of reliable data presented here are extremely compelling, O’Reilly concluded, and the MDRC research will be valuable as Congress proceeds to debate the future of federal educational policy.

Highlights from the Question and Answer Session

A question was asked as to the extent to which Career Academies link their curriculum to the needs of local employers. Kemple responded that many Academies were created specifically to respond to regional demands for skilled workers in certain fields. However, he added, most Academies have observed over time that large numbers of students drift away from the particular job sector that the curriculum aimed to serve—that’s not necessarily a negative outcome, though, Kemple argued; it should count as a success if students learn about a given job sector and then make an informed decision to pursue a different career. Agreeing with Kemple, Hoye termed it a “successful failure” when students opt out of the given career path and choose instead to go into another line of work or to go to college.

Another questioner pointed out that the MDRC study reported on long-term outcomes for students who attended Career Academies many years ago. How, he asked, has the Academy model changed since then? One important change has to do with the nature of classroom instruction, said Dayton. In the 1990s, the teaching that went on at Academies was more or less the same as the instruction that occurred in other schools. But since that time, Career Academies have come to emphasize classroom instruction that integrates academic and job-related content. Hoye added that Academies now provide teachers with much better and more frequent professional development opportunities than used to be the case. However, said Kemple, recent changes may be putting Career Academies at risk of losing their distinct mission and identity. The model has stood at the intersection of various high school reform strategies, such as integrative teaching and the creation of small learning communities. Many Academies have emphasized such popular strategies in order to take advantage of new funding opportunities, and this may lead them to spread themselves too thin, Kemple warned, and to stray from their core focus on career preparation.

Another questioner wondered how much of a benefit students receive from employer mentoring programs. According to Dayton, in the California Career Academies students are supposed to be assigned a mentor in the 11th grade and then complete an internship with them over the following summer. When done well, he added, the benefits are substantial, especially insofar as students develop the kinds of “soft” skills (such as interviewing, dressing appropriately, and getting to work on time) that will help them obtain and keep jobs in the long run.

A hypothesis was offered as to why Career Academies were found to have much stronger benefits for males than females. The MDRC data shows that males were much more likely than females to choose classes and internships in computing, technology, and other fields that may translate to higher earnings in the long run, while females seem to have gravitated to lower-paying occupations such as travel services and small business ownership. That hypothesis may be worth exploring, agreed Kemple, but the MDRC research didn’t turn up any relationship between the particular job sectors that each Academy emphasized and their students’ long-term outcomes. Much more telling, he said, is the differential between those students who remained in the program throughout high school and those who left early, and this may help to explain the difference in outcomes between males and females.

Finally, a questioner asked whether the students in the control group received the same sort of college and career advising services as those who participated in Career Academies. In this respect, the two groups were very comparable, said Kemple. Because most Academies are set up as a school-within-a-school, participating students and those in the control group continued to belong to the same campus, which means that both groups of students received the same college advising services—even though in most high schools, such services were negligible. On the other hand, Kemple added, students participating in the Academies may have received additional college advising of a sort by virtue of their relationships with mentors, some of who may have offered information of the kind that a well-trained guidance counselor might provide.

Charles Dayton, Coordinator of Public Programs, University of California–Berkeley. Mr. Dayton is currently a Coordinator of Public Programs at UC Berkeley, and has been the Coordinator of the Career Academy Support Network (CASN) in the Graduate School of Education there since 1998. CASN assists Small Learning Communities (SLCs) and Career Academies nationally and in California through professional development; a web site (casn.berkeley.edu) with a national directory of academies, a variety of guides and handbooks, and an on-line inquiry service; and evaluations of SLCs/ Academies. CASN also works with a variety of other state and national agencies interested in high school reform in general and SLCs and Career Academies in particular.

Mr. Dayton is a former English teacher (Auburn, NY), Research Scientist (American Institutes for Research, Palo Alto), and Education Consultant (Foothill Associates, Nevada City, CA). His work has focused on high school approaches designed to motivate at-risk students to prepare for college and careers. He helped to organize the first Career Academies in California, the first state level support for them, and conducted statewide evaluations of the California Partnership Academies for several years for the California Department of Education. He has written a number of journal articles and contributed to several books, including Career Academies: Partnerships for Reconstructing American High Schools (Stern, Raby, & Dayton, 1992). Mr. Dayton has two grown children, both Stanford graduates, and lives with his wife in Nevada City, CA.

JD Hoye, President, National Academy Foundation. JD Hoye has a lifetime commitment to preparing students for meaningful careers. A nationally recognized leader in forging partnerships between educators and employers, JD has worked on both a grassroots level and at the highest levels of government trying to reform how our children learn about, prepare for, and pursue their career goals. Ms. Hoye joined the National Academy Foundation in January, 2007.

Prior to assuming her leadership role at the National Academy Foundation, Ms. Hoye served as President of “Keep the Change”; a nationally recognized consulting business focused on helping communities reform education and develop a top-notch workforce. A much sought-after public speaker, Ms. Hoye worked closely with the National Academy Foundation while President of “Keep the Change” and developed strong relationships with the Foundation and its leadership.

Ms. Hoye developed and implemented policy at the highest level of federal government. In 1994, she was selected by U.S. Secretary of Education Richard Reilly and Secretary of Labor Robert Reich to head the new Office of School-to-Work in Washington, D.C. She served in that role for four years, overseeing a $1.1 billion budget and nationwide program that partnered education reform with workforce development.

Ms. Hoye has also been a leader for education reform on a state and local level. She served as Associate Superintendent of Oregon’s Department of Education, where she managed the Office of Professional/Technical Education and Community Colleges. Additionally, she served as the leader of a 27-county organization that managed federal job training funding for rural counties in Oregon.

Ms. Hoye’s commitment to the tenets of the National Academy Foundation’s goals can be traced to her first job and her first love – working to make children’s lives better. She began her career as a youth employment counselor working directly with at-risk youth in Corvallis, Oregon where she saw firsthand the need to connect youth with school and with careers.

James Kemple, Director, K-12 Education Policy, MDRC. Dr. Kemple leads MDRC’s work in K-12 education, with expertise in evaluation design, site selection and engagement, experimental and quasi-experimental impact analyses, field research, and project management. Dr. Kemple led the site selection process for the National Reading First Impact Study and serves as co-director for that study, which MDRC is conducting with Abt Associates. He advises on evaluation design and site selection for the demonstration and evaluation of Academic Curricula in After School Programs and for the evaluation of Professional Development for Early Grade Literacy.

Dr. Kemple has served as principal investigator for MDRC’s Career Academies evaluation and for the evaluation of the Talent

Development Middle School and High School models; he also advises on research design and impact analysis for MDRC’s evaluation of Project GRAD and Scaling Up First Things First. In earlier work for MDRC, Dr. Kemple coauthored the final implementation report on the National Job Training Partnership Act study; managed an implementation and impact evaluation of Project Independence, Florida’s JOBS program; and was the impact analyst for an evaluation of Florida’s Family Transition Program, the nation’s first time-limited welfare reform initiative. Prior to joining MDRC, Dr. Kemple taught high school math and managed the Higher Achievement Program, a three-phase academic and high school placement program for disadvantaged youth in Washington, DC. He coordinated a qualitative implementation study of the Boston Public School Curriculum objectives for the Citywide Education Coalition, and, with Richard Murnane and others, he coauthored Who Will Teach? Policies That Matter.

Resources

Career Programs Stress College, New York Times Article.

MDRC/James Kemple, Power Point presentation.

Bradby, D., Malloy, A., Hanna, T., & Dayton, C. A Profile of The California Partnership Academies, 2004-05. ConnectEd California, 2007 (available at casn.berkeley.edu). Compares the ~33,000 students in career academies in California with statewide averages.

Maxwell, N. & Rubin, V. High School Career Academies: A Pathway to Educational Reform in Urban School Districts? W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, Kalamazoo, MI, 2000. Compares students in four “tracks” in a large urban district over several years: i.e., college prep, vocational, general, and career academy.

Stern, D., Dayton, C., & Raby, M. Career Academies: Building Blocks for Reconstructing American High Schools. Career Academy Support Network, UC Berkeley, 2000 (available at casn.berkeley.edu). A summary of the history of career academies and research to that point, plus implications for educational policy.

MDRC – Career Academies long-term impacts on labor market outcomes, educational attainment, and transitions to adulthood; James J. Kemple

The California Partnership Academies 2004-2005

Career Programs Stress College, New York Times Article

MDRC – James Kemple, PPT

Stern, D., Dayton, C., & Raby, M. Career Academies: Building Blocks for Reconstructing American High Schools. Career Academy Support Network, UC Berkeley, 2000 (available at casn.berkeley.edu). A summary of the history of career academies and research to that point, plus implications for educational policy.

Bradby, D., Malloy, A., Hanna, T., & Dayton, C. A Profile of The California Partnership Academies, 2004-05. ConnectEd California, 2007 (available at casn.berkeley.edu). Compares the ~33,000 students in career academies in California with statewide averages.

Maxwell, N. & Rubin, V. High School Career Academies: A Pathway to Educational Reform in Urban School Districts? W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, Kalamazoo, MI, 2000. Compares students in four “tracks” in a large urban district over several years: i.e., college prep, vocational, general, and career academy.

Charles Dayton

Coordinator, Public Programs

University of California-Berkeley

Career Academy Support Network

Graduate School of Education

230 Main Street, Suite 2A

Nevada City, CA 95959

530-265-8116

JD Hoye

President

National Academy Foundation

39 Broadway, Suite 1640

New York, NY 10006

212-635-2400 X861

James Kemple

Director

MDRC

K-12 Education Policy

16 East 34th Street, 19th Fl.

New York, NY 10016

212-532-3200