Overview

The American Youth Policy Forum (AYPF) and the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) facilitated a series of field trips around the country to help state policy leaders learn more about high school redesign. This project, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, supported The Honor States Program, an initiative of the National Governors Association (NGA) Center for Best Practices, by providing hands-on professional development activities to state teams comprised of governors’ staffs, members of state education boards and commissions, state legislators, and senior legislators, and senior state officials working in K-16 education.

The fifth field trip in this series was to Indianapolis, Indiana, and was designed to bring state legislators together to visit redesigned high schools and engage in policy discussions with state and district leaders working to improve high school graduation and college-readiness rates throughout the state. State legislators from Louisiana, Mississippi, Virginia, and Rhode Island participated on this trip.

Purpose

The purpose of this trip was to expose state legislators to policies, legislation, and practices in Indiana that support high school redesign, provide time to learn about the context of the reform, and encourage peer-to-peer learning and networking among participants. Specifically, the trip was designed to enable participants to learn about the following:

- Indiana’s rigorous default high school curriculum (Core 40) for all students to ensure more young people graduate from high school college- and career-ready; and

- Indiana’s new comprehensive dropout prevention and recovery legislation.

The trip enabled participants to see a number of programs intended to increase the number of students graduating with a high school diploma. It also provided a forum to meet with state and education leaders, researchers, and state legislators who are working at the forefront of these issues in Indiana. Meetings with policy leaders provided time to delve deeper into the strategies and policies used to support high school redesign in Indiana.

Overview of Indiana’s High School Redesign Agenda

The trip began with a meeting with four representatives of the Indiana Education Roundtable, representing the Office of Public Instruction, Office of Higher Education, State Board of Education, and the Governor’s Office. They met with the group to provide a historical overview of Indiana’s high school reform agenda and provide context for the two-day visit.

Dr. Suellen Reed, Indiana Superintendent of Public Instruction, opened the session with historical information about the state’s strategy for creating a high-quality education system for all high school students by creating rigorous state standards. Beginning in the late 1980s, business, higher education, and K-12 leaders came together to identify what students needed to know to prepare them for postsecondary education or employment in Indiana. Based on their findings, the state developed a set of standards and a more rigorous college-preparatory curriculum consisting of core courses in English, mathematics, science and social studies. The Indiana state legislature ratified the college- and work-ready curriculum, which they called the Core 40 curriculum, in 1994. “The business community was the driving force behind Core 40, initially,” Reed stated. This was the beginning of Indiana’s strategy of bringing a variety of stakeholders to the table.

Although participation in Core 40 was originally voluntary, the state strongly encouraged schools to offer the courses and students to take them. As a result, the percentage of students earning a Core 40 or more rigorous Academic Honors diploma rose from 13 percent in the 1993–94 academic year to 65 percent in 2003–04. Since the 1980s, when this work began, Indiana has moved from 40th to 10th in the nation in the percentage of high school graduates going to college (Achieve, 2005).

In 1998, Reed and then-Governor Frank O’Bannon formed the Indiana Education Roundtable as a way to invite all stakeholders, including K-16 leaders, legislators, lobbying groups, and business leaders to the table to address education problems together. At that time, there was a great deal of blame and “finger pointing” between the various groups, and this was a way to “focus all of that energy on what really mattered—the kids” said Reed. The Roundtable was formalized by legislation in 1999, and the group was charged with making recommendations to the Governor, Superintendent of Public Instruction, General Assembly, and Indiana State Board of Education. According to Reed, the focus of the Roundtable was to answer the question, “What can we do for our children that will make them as successful as possible in the 21st century?”

First the Roundtable discussion focused on improving state standards and creating voluntary end-of-course assessments in Algebra I and English II to hold schools accountable and ensure that students were learning high-quality content consistently across schools. “We wanted to make sure that if students were taking Algebra, they were really learning algebra and not business math or something else,” Reed said. The state is in the process of developing additional end-of-course assessments in Algebra II, Biology I and U.S. History. Currently, end-of-course assessments in core subjects are voluntary and students do not need to take them to earn the Core 40 diploma; however, the state is moving toward policies that would require students to pass the assessments in order to earn the Core 40 diploma. Cheryl Orr, Liaison to the Education Roundtable, stressed that requiring end-of-course assessments will “allow for more quality control as schools are compared across districts.”

Next the Roundtable focused on the alignment between high school and college- and workforce-readiness to improve the Core 40 curriculum. Orr noted, “Indiana is slowly evolving from a manufacturing and agricultural state to one that believes everyone should be work and college ready when they graduate from high school.” However, the state did not want to define “rigorous curriculum” too narrowly. As a result, they expanded the Core 40 curriculum to offer both the Core 40 with academic honors curriculum and the Core 40 with technical honors curriculum. This flexibility allows students to take rigorous hands-on, applied courses as well, if they wish. The flexibility is also “necessary to helping kids stay connected and not dropping out, noted Jeff Zaring, Administrator to the Indiana State Board of Education. He furthermore noted that it was very important to the state of Indiana to give the technical honors and academic honors programs the same “weight,” or level of importance.

Orr explained that in 2005, the Indiana Education Roundtable recommended that the state make Core 40 the default high school curriculum for all students as part of a broader P–16 Plan for Improving Student Achievement. The Indiana Legislature approved this recommendation to be implemented in the 2007-08 school year for all incoming ninth graders, thereby making the graduating class of 2011 the first mandatory Core 40 class in the state. And to further accentuate the importance of the Core 40 diploma, beginning in fall 2011, this curriculum will become an admissions requirement for all public, four-year colleges and universities in Indiana.

Indiana has also removed low-level math classes from high schools, encouraging all students to take Algebra I in eighth grade. The elimination of lower-level math classes in high schools created a need to streamline the transition from middle school to high school and offer additional courses, or “helping courses,” for students who need extra support. However, these “helping courses,” which are technically remedial courses, do not count toward the graduation requirements. In order to give teachers incentive for teaching the more rigorous courses, some schools are equipping them with teacher coaches and also offering student loan forgiveness.

Another recent addition to Indiana’s high school reform strategy is dual credit/dual enrollment. As of right now, there is not yet a complete system in place for dual enrollment, but this is mostly due to the fact that Indiana’s community college system is still in its early years, having been newly implemented in 1999. Even so, the state regards the offering of dual credit courses as an opportunity for encouraging high school students to continue on to college and for allowing entering college students to get off to a good start. The enthusiasm for the flexibility of the new dual enrollment program is one way that Indiana is demonstrating its belief in high education standards and high levels of attainment for all.

One way that the state of Indiana is working to increase the numbers of low-income and minority youth entering college is through the 21st Century Scholars program, which was created through legislation in 1990. Through this program, seventh and eighth graders make a pledge of good citizenship, finishing high school, and maintaining at least a 2.0 GPA all the way through; if they succeed, they are guaranteed four years of college tuition (paid by the state) at any public Indiana college (or an equivalent award at any private or proprietary Indiana college). The money does not cover room and board, but many foundations have stepped up to cover those costs, further easing the pathway to college for these students. Currently, about 20 percent of Indiana’s seventh – eighth graders are eligible to participate in the 21st Century Scholars program, and 50 percent of those eligible actually do participate (this is 10 percent of the total Indiana seventh – eighth grade population).

Learn More Indiana is another state initiative; it is a campaign to provide parents and students with information to support successful transitions during and out of high school. It is a partnership between the Indiana Department of Education and the Indiana Commission of Higher Education. The campaign provides free handouts to help empower students and parents by directing them to the free career and education resources available at Learn More Indiana’s website (www.learnmoreindiana.org). Resources include Student Success mini-magazines, which are a series of grade-specific guides helping parents understand what is required of students in each grade to successfully transition to the next. For example, the eighth grade guide provides a helpful checklist for students to know what to do and when to successfully transition to high school and other pertinent information.

Lessons Learned by the Indiana Education Roundtable

- Make sure all key stakeholders, including critics, are involved in the planning and implementation of major education decisions. Indiana’s Education Roundtable decided early on to make decisions by consensus, which was not always easy, but has effectively ensured buy-in from key constituent groups. “You can get marvelous things done if you don’t care who gets the credit,” said Suellen Reed.

- Invite noted experts and researchers to meet with and present to the group from time to time as a way to broaden the group’s thinking, provide new learning opportunities to the group, and help ground decisions in research.

- Put the data systems in place as a way to improve decision making, create early warning systems, and communicate changes and rationales for change to the public.

- Keep the focus on the big picture questions, such as what can we do for our children that will make them as successful as possible in the 21st century? “Higher standards were never our goal—getting kids ready for work and college was,” said Jeff Zaring.

- Ensure that technical honors and academic honors curriculums have the same importance. This has been a critical aspect of the state’s reform.

Peer-to-Peer Learning Session

Alex Harris, Senior Policy Analyst, National Governors Association, opened this peer-to-peer learning session with a short description of the Honors States program, noting that $25 million in challenge grants has been awarded to 26 states for HS redesign. This money is being used for a plethora of different projects; while some are focusing on STEM curriculum, for example, others are funding bottom-up, community-driven reform efforts. Alex then turned the conversation over to the state representatives to share what education efforts are taking precedence in their states right now.

Joseph McNamara, State Representative for Rhode Island, noted that Rhode Island has a 35-40 percent dropout rate in the urban areas of the state. “This is by far our biggest issue,” he said. “I think we’re letting kids off the hook too easily and not addressing their true needs.” McNamara offered a few ideas he has been an advocate for, such as ensuring that failing students meet with their counselors often to hear about the options they have for their futures, as well as expanding internship opportunities for high school students as exciting ways to keep them engaged in school. This an especially valuable idea for English Language Learners (ELL), he said, because they are often valued in their internship placements for knowing two languages, and this helps to build their self-esteem.

In addition, Rhode Island is developing new college-ready standards of performance in math, reading, and writing, which compare favorably with the American Diploma Project. The state is focused on STEM curriculum as well and is launching a “Physics First” initiative aimed at creating a new curriculum sequence for high school science, beginning with Physics in ninth grade. With the help of the East Bay Educational Collaborative, Rhode Island will provide intensive professional support to teachers and department heads from five participating pilot schools. Working with Jobs for the Future, the state conducted a review of current dual enrollment activities around the state and found uneven quality and access for students. Leaders are outlining action steps to improve and expand such options and to address this concern.

A.G. Crowe, State Representative for Louisiana, said that a major issue in his state right now is still the Hurricane Katrina aftermath and its negative effects on the education system. One state-run recovery school, he noted, is having trouble finding existing documentation about its students, as much of it was destroyed. They sometimes are not even sure what grade the student was in at his former school before the hurricane, Crowe stated. Regina Barrow, another Louisiana State Representative in attendance, added that another problem the state is facing is youth not attending school again when they come back to the state from their evacuation during Katrina.

Despite the difficult challenges Louisiana is facing right now, the state has a unique opportunity to redesign its high schools. For instance, the New Orleans school system is using a system of choice, and a strong coalition of key stakeholders and policymakers is guiding the state policy work through the High School Redesign Commission. Alex Harris mentioned that Louisiana’s new data system for high school accountability is a model for the country. “Underlying this data system is a model that better aligns the goals of rigor and dropout prevention by creating an early warning system to detect students at risk of dropping out before they enter high school,” said Harris.

On another note, Crowe said that he sees using technology in innovative ways as a viable and necessary way to keep high school students interested in school, as well as to keep school relevant to them. He suggested that the internet could possibly be more widely utilized as a reference tool than it is currently.

Mike Lott, State Representative for Mississippi, shared his state’s issues with the group. “We’re the poorest state in the nation,” he reminded the participants. Even so, Mississippi has increased its education budget every year for the past three years, he said. Additionally, Lott noted that there has been a 38 percent total pay increase for teachers in the last five years. This coming session, the state will tackle legislation on high school redesign, but this has so far not been budgeted for. One recent change to the state’s education system is a new law that allows school districts to partner with private entities. This, along with Mississippi having a strong data-based accountability system that is helping to show off the positive results that the state is seeing, is aiding in attracting local businesses to get involved with their local schools and education as a whole. Lott considers this a move in the right direction for the state.

Adam Ebbin, State Delegate for Virginia, talked about his state’s goal to build high school teaching and leadership capacity as a method for improving high school graduation rates. Specifically, the state has identified all high schools with higher than average ninth-grade retention rates and has selected 30 such high schools as the state’s primary focus for reform using their honor states grant. These schools represent 10 percent of the total high schools in the state. Challenge grant funds are being used to expand existing intervention strategies and pilot new approaches for the purpose of studying promising school-level practices and then replicating them through state policy changes.

Lunchtime Briefing with Jonathan Plucker, Terry Spradlin, and Ethan Mintz of the Center for Evaluation & Education Policy, Indiana University

Our group met with three presenters over lunch from the Center for Evaluation & Education Policy (CEEP), which promotes rigorous program evaluation and education policy research for educational, human services, and nonprofit organizations. As part of the Indiana University School of Education, CEEP represents nearly 40 years of leading-edge evaluation and research experience focused on research trends in the state of Indiana and nationally.

Jonathan Plucker, director of CEEP and professor of educational psychology at Indiana University, started off by providing an overview of what’s working in Indiana based on their findings from researching high school redesign in the state.

The Good News in Indiana

- The increase in the number of students completing more rigorous courses and AP courses is attributed to the Core 40 and Academic Honors Diplomas.

- SAT, ACT, and ISTEP+ (Indiana’s state test) scores have risen in the past three years.

- More students are going directly to post-secondary schools after high school than in the past.

- People recognize the high dropout rates: in a statewide survey, 89 percent of Indiana residents indicated that the high school dropout rate is a significant issue; 92 percent of those 18 – 34 consider is a significant issue; and 92 percent of non-White respondents report that it is a significant issue.

Although Indiana has made progress, the presenters also shared data and research demonstrating why more reform is necessary. Namely, there are persistent achievement gaps, high school dropout rates are still high, suspension and expulsion rates are high and disproportionately affect minority students, there is a lack of student engagement, and there are high college remediation rates.

Nationally, by the end of Grade 8, low income students and minority students lag behind their peers by three grade levels, and by the end of Grade 12 they lag behind by four grade levels. While students across all racial categories have continued to improve on the ISTEP+ exam, there remain 25 percent and 27 percent gaps between White students and minority students in reading and math, respectively.

Terry Spradlin discussed research findings that show correlations between the use of suspensions and higher dropout and juvenile incarceration rates. In addition, districts that practice more in-school discipline measures, such as Saturday school, experience decreases to their dropout rates. Dr. Spradlin told the group Indiana’s broad use of out-of-school discipline practices are an issue the state still needs to address. “For the 2000-2001 school year, Indiana had the highest expulsion rate and the ninth highest out-of-school suspension rate in the nation. Changes to disciplinary policies are an area where schools could potentially improve the number of students staying in school,” he said.

Finally, recent research indicates that many high school students are not engaged in classes and learning at school, which leads them to drop out. Dr. Ethan Mintz discussed the High School Survey of Student Engagement (HSSSE), a project of CEEP that studies the engagement of high school students in academic activities and provides information to help guide school improvement. In 2005, HSSSE was administered to 80,904 students in 19 states and found two important indicators of high school students’ lack of engagement. First, 50 percent of students reported that they spent fewer than five hours each week preparing for class, yet over 80 percent said that they complete homework assignments before class. These findings suggest that the expectations of homework assignments are not challenging enough to engage high school students. A second indicator of academic engagement is student participation in class assignments and discussions. Forty-two percent reported that they had sometimes or never integrated information from a number of sources for a project and only 50 percent said they regularly participate in regular classroom discussions. Strategies that increase the amount of time students spend preparing for classes, as well as synthesizing and discussing coursework, could also be employed to increase the number of students staying in school.

Brokering Policy Change through Legislation with Stanley Jones, Commissioner of Higher Education and Indiana State Representatives Luke Messer and Greg Porter

After lunch the group went to the Indiana Department of Higher Education to meet with Stanley Jones, Indiana’s Commissioner of Higher Education and State Representatives Luke Messer and Greg Porter to learn more about the state’s dropout prevention and recovery efforts and 2006 legislation. Representative Luke Messer introduced HB 1347, a dropout prevention and recovery bill, in the 2006 legislature with the bipartisan support of Representative Greg Porter. Jones provided much needed support and leadership from the higher education community, which was critical to the successful passage of the legislation (149:1 vote).

Until 2005, Indiana had reported a graduation rate of 90 percent, a figure that did not include students who dropped out before their senior year. Dr. Stanley Jones opened the session by stating, “The dropout issue isn’t new; what’s new is that people are now aware of it.” He went on to say that states across the country have historically, and erroneously, reported graduation rates in the 80 percent-90 percent range. “Indiana is not unique in that its reported graduation rates severely understated the problem,” he said. Current research shows graduation rates are around 70 percent, but can also be around 50 percent and in some cases less than 20 percent, in some local districts and schools.

Messer continued to present a snapshot of the state’s dropout issue. As an example, he showed the group enrollment trend data from five anonymous Indiana high schools, from a variety of regions, which showed a steady, though at times dramatic, decline in the number of students in grades 9 through 12 and on through graduation. “In one school, there were 875 students in ninth grade, but only 100 students graduated four years later” he said. “The numbers tell the story better than any of us can,” he continued.

Messer also discussed the societal costs of high dropout rates, such as costs of public assistance, health care, and incarceration. “It’s important to remember that just because a student drops out of high school does not mean that our job as a state is over. I think we could all agree that we would rather be spending money on schools rather than our over-crowded jails and prisons.”

In 2005, the General Assembly passed a bill, HEA 1794, that required calculating dropout rates by using the number of incoming freshman and comparing that to the number of seniors graduating four years later. The new method revealed that Indiana’s graduation rates was closer to 70 percent, a number far lower than previously reported. “The codification of dropout numbers created a sense of urgency amongst responsible parties. Education leaders knew that new numbers were coming out and wanted to get to the table and have a voice in the solution,” said Jones. The passage of this legislation led the state to confront the reality of a dropout problem and laid groundwork for future legislative action to address the dropout issues.

Additional HEA 1794 Provisions

- Raise Legal Dropout Age - One solution in Indiana was to raise the legal dropout age from 16 to 18, and to tighten restrictions on reasons students can leave school. “The 16 year old dropout age was based on a set of assumptions that were true about the job market 30 years ago, but are now grossly out of date,” said Messer.

- Change Withdrawal Process – Indiana now requires potential dropouts to go through an exit interview. Students and parents must talk with the principal about the economic consequences of dropping out.

- Driver’s License/Work Permit – Students who drop out without the permission of their parents or guardians and principals can lose their driver’s licenses and work permits if they cannot demonstrate financial hardship as the reason. Messer says this requirement also makes principals more accountable for dropout rates.

- Chronic Absenteeism – Students who miss more than 10 unexcused days of school are in danger of losing their drivers’ licenses and work permits as well. Jones explained that chronic absenteeism was an early warning that students were at risk greater of dropping out. “We did focus groups with dropouts and the average number of days that they were absent in the year prior to dropping out was greater than ten. It was a critical factor,” he said.

- School Flex – “School Flex” created an alternative program for students in Grades 11 and 12 that aimed to engage students in relevant learning by allowing them to enroll in a college/technical career center or employment, while the high school continues to count (and pay for) the student as a full-day student.

Nonpartisan Consensus Building and Public Support

Throughout summer and winter of 2005, Representative Messer and Dr. Jones met with students, teachers, the teachers’ union representatives, superintendents, principals, and representatives of universities, state Black Caucus members, state Hispanic Commission members, editors from the Indianapolis Star, and other legislators to elaborate on the scope of the dropout problem. These meetings were an effort to educate key stakeholders and the public on the issue, garner support on a solution to the dropout problem, and lessen opposition to a new legislative solution. In fall 2005, the Indianapolis Star ran a weeklong front page series on the dropout numbers in Indiana and helped put a personal face on the problem.

Building consensus was a lengthy process, but a critical one. Initial political pushback came from democrats in the state House of Representatives, especially members of the state Black Caucus, as well as the teacher and principal groups. Representative Porter, who is also the leader of the state Black Caucus, stressed the importance of getting the group to support a new piece of legislation. “We have known there was a dropout problem in our city for years; this was nothing new to us. When Representative Messer introduced his ideas for improving the problem I, for one, was very suspicious and I questioned, ‘where’s the hidden agenda?’ Since I was suspicious, the other members of the Caucus were suspicious too,” said Porter.

Messer agreed that getting Porter onboard with proposing any legislative solution, thus garnering bipartisan support, was critical if they were going to move forward with any new legislation. “We were playing this game with all our cards up. There are no hidden agendas,” said Messer. After hours of debates and discussions about how to improve opportunities for youth and improve graduation rates in the state, Porter became a full supporter for the dropout legislation and helped to gain buy-in from other reluctant groups.

The group also worked to gain buy-in from the general public, and one way they went about this was through focus groups with young people who had dropped out of high school just one to two years earlier. “Over and over again we heard a loud and clear message that these young people were remorseful about dropping out of high school. They realized that a high school diploma was important, but felt like it was too late to go back to high school,” said Jones. “When asked whether they would get a high school diploma over a GED if the process were as straightforward, they said a resounding ‘yes’.”

As such, in 2006 Jones, along with Messer and Porter, worked together to introduce HB 1347, a new dropout prevention and recovery bill, building on HB 1794 that had bipartisan support and the support of the higher education community.

HB 1347, Now Current Law

- Annual School Report Card – This requires high schools to annually report a number of new factors on their school report cards: total suspensions, students permitted to dropout by the school, number of work permits and driver’s licenses revoked, number of students in the Flex Program, freshmen not earning enough credits to become sophomores.

- Review of Student Career Plan – A designated school counselor is required to review each student’s career plan. If a student is not progressing, the student is counseled about credit recovery options and services available so that he or she may graduate on time.

- Fast Track – This provision sets up high school completion programs at community colleges so students who have dropped out can earn regular high school diplomas instead of GEDs. This addresses many of the concerns over the difficulty of getting back on track to a high school diploma once students had dropped out.

- Double Up – Double Up allows students to earn credit toward associate’s degrees while still in high school, at no cost to low-income students. It also requires high schools to offer a minimum of two dual credit and two AP courses so that students may meet the requirements to earn a Core 40 with academic honors diploma.

The presenters did address the fact that some schools have indeed purposefully pushed kids out of the school system by signing them out and encouraging them to dropout. This is why the 2006 legislation requires schools to submit this data on their annual report cards. “There needs to be accountability around how many students are leaving schools with permission from the principals. This information needs to get tracked so we have checks and balances,” said Porter.

Indiana’s liberal home school policy and the strength of the home school lobby groups came up several times during the discussion, especially since the state has few monitoring and accountability provisions regarding home schooling. “Parents can withdraw their children from the school system to put them in home school and the school can’t ask too many questions,” said Representative Porter. In this case, it can make tracking dropouts a little more difficult since some students who are actual dropouts might easily be counted as students in home school.

Lessons Learned

- Talk about the problem and invite everyone to the table. Invite school faculty, staff, parents, students, and community members to have open conversations focused on possible solutions.

- Examine the data. Through the school annual report cards and data systems, school leaders can slice and dice the numbers to see who is dropping out, when they are dropping out, and what indicators are present before they drop out (chronic absenteeism, suspensions, etc.).

- Think outside the box. Find new ways to help students beat the odds by considering ways to help kids who are behind on credits, seem unchallenged by the curriculum, or just get lost in the shuffle.

- Ask questions and seek promising practices. Ask colleagues from other districts and states what they are doing and what is working in their jurisdictions.

- Connect to the full spectrum of the K-16 education system. In Indiana, Stan Jones is a leader in the dropout prevention and recovery discussion, which is critical to getting high education involved in creating and implementing solutions. “Colleges want more diversity on their campuses so it’s in their best interest to be involved in thing like Core 40 legislation, dropout recovery discussions, and other similar high school reform policies,” said Jones.

Site Visit to Lawrence Early College High School for Science and Technologies

The next morning the group visited Lawrence Early College High School for Science and Technologies (LEC) in Lawrence Township, about one hour outside of Indianapolis. LEC is a small, autonomous high school that blends high school and college while focusing on Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) courses and skills. The school is designed so that all students have the opportunity to gain up to two years of college credit at the same time they are earning a high school diploma. LEC, opened in August 2006 in collaboration with the Metropolitan School District of Lawrence Township (MSDLT) and Ivy Tech Community College of Central Indiana, was Indiana’s first early college high school.

LEC is an open enrollment charter school whose charter was granted by the Mayor. The school currently has 154 students in Grades 9 and 10 and plans to add one grade each of the next two years for a maximum enrollment of 400 students in Grades 9 through 12. The school is open to all students, but it is specifically designed to meet the needs of those students for whom a smooth transition to college may be challenging. Special recruitment efforts are targeted toward students who are the first in their families to attend college, students who are traditionally underrepresented in the college population, and students who may find the cost of college a barrier.

Dr. Kay Harmless, Director of LEC, met with the group to give a brief overview of the school’s mission, design structure, and operating principals. The mission of LEC is to provide a unique supportive learning community in which high school students take rigorous academic content, earn college credit, and gain life and career skills necessary for success in the 21st century workplace. Harmless described the approach to instruction as “inquiry-based, mirroring the scientific method, with teachers as coaches.” All students are required to take the rigorous Indiana Core 40 courses, as well as the required state assessments. All students enrolled in LEC will have the opportunity to achieve up to two years of college credit at the same time they are earning a Core 40 Indiana diploma.

Several LEC students led small groups of participants through the school to observe classes and view the facilities. The STEM focus is central to the curriculum and technology is integral to teaching and learning. The school offers a one-to-one technology ratio (one computer per student), online and virtual learning classes, and an emphasis on high-skill careers. It shares the building with the McKenzie Career Center, a career program within MSDLT. The two schools operate autonomously; however, they share facilities such as the auditorium, cafeteria, and other common areas.

Next, participants met with a number of stakeholders at the school, including students, Ivy Tech college representatives, and teachers and counselors and LEC to learn more about their perspectives of the new school. During discussions, many students stressed how important it is to keep the school small. They also mentioned that the teachers care about them and about their future success and are preparing them to enter any career because of the school’s strong emphasis on math, science, and technology, critical thinking, and problem solving. Career pathways, such as biotechnology, computer technology, and visual communications/graphic design, are made available to students, with these “pathways” beginning as electives in high school and extending to advanced studies at the community college.

Site Visit to Shelbyville High School and the Shelbyville Student Achievement Center

The final visit for the day was to Shelbyville, Indiana to see Shelbyville High School and the Shelbyville Student Achievement Center. In April 2006, Shelbyville High School was featured in a Time Magazine article titled, “Dropout Nation” and was highlighted in an episode of the Oprah Winfrey Show on the same topic later that month. Shelbyville is a middle-income community and most people would not predict that it has a dropout problem, yet the district was willing to review the data, admit the problem, and discuss the issues in an open forum.

Mr. Tom Zobel, Principal of Shelbyville High School, met with the group to provide an overview of the school. Shelbyville High School (SHS) enrolls over 1,000 students in Grades 9-12. Ninety percent of the students are White and 10 percent are minority, with Hispanics as the largest minority group. The special education population at SHS is 22 percent, higher than the state average. The community has a stable population—over 50 percent of students had the same residence in 2000 as they did in 1995. About 30 percent of the students at SHS qualify for free or reduced price lunch, and SAT and ACT test scores are above the state and national averages. In the 2005-2006 school year, 34 percent of the students took AP classes, and of those students, about 42 percent scored a 3 or above on the AP test. Ninety-one percent of SHS class of 2006 graduates went on to post-secondary education—a four-year college, two-year college, or technical certificate. Yet, despite such promising statistics, one out of three students who enter the high school in the ninth grade don’t graduate from high school in four years” said Mr. Zobel.

In August 2005, Mr. Dave Adams was named Superintendent of Shelbyville Public Schools. Adams previously was the principal at Shelbyville High School for ten years. When Adams took the position, he began with a focus on the school corporation as a K-12 system and went through a SWOT analysis and data analysis process. “Armed with the data, we were able to develop a strategic plan and roll out reform efforts that the community would support,” said Adams. The reform efforts to address the dropout problems were as follows:

- Credit Lab – They established a credit lab on campus for students to make up credits that they were missing or failed to receive in a timely manner. “Every credit that a student falls behind is a greater chance that they will drop out,” said Adams.

- Elementary School Retention Philosophy – After looking at who gets retained and the research on retention showing that retention leads to more dropping out, they established a new retention philosophy for the school corporation that favored intense remediation and early intervention instead of retention.

- School Day Start Times – The district decided to change the start time for secondary schools by opening later in the morning following research on adolescents’ sleep needs, and after a Minneapolis suburban district that shifted its high school start time by more than an hour several years ago found absenteeism and dropout rates declined, while student alertness improved.

- High School Student Achievement Center – They established an alternative high school center, located off the SHS campus, for students to work at their own pace to graduate. This center is for students who have dropped out of SHS and have a few more credits to earn a high school diploma. It is also an alternative to traditional suspension, in which students stay at home during the day. Instead they can continue learning, through independent study, in the Student Achievement Center. At the center, each student has a computer and quiet space to do class assignments, study, and work on projects. The center is flexible and students are able to use it as needed based on their other obligations: many students have jobs that require them to work during the day as well as evenings, while other students are parents and have family obligations of their own. There are no state funds specifically for the Student Achievement Center, but with the new legislation that supports dropout recovery efforts, the district is hoping to use such funding in the future.

- Review Corporation Discipline Philosophy and Beliefs – The school district is planning to have a formal review of its expulsion and suspension policy. Adams would like to ensure that the district develops a clear belief system that expulsion is a rare disciplinary action because the adults in the system believe in the abilities of every student. He would also like to explore the option of using the School Achievement Center as a mandatory suspension alternative.

- Wrap-Around Services – “Out of the 10 reasons that students drop out, eight have little to do with school,” said Adams. “That’s why it’s important to work with the community service agencies and the juvenile court system.” Adams is creating a process by which the school system works with the court system to better align an education schedule for kids who go to court.

- Corporation Grading Scale – The school district is examining the current grading system, which is higher than many others in the states, and looking into changing it to match the neighboring grading systems. Currently, anything below 70 percent is a failing grade.

- Curricular Reform – Zobel discussed the need to also improve curriculum and instruction in the high school so all students receive the same high-quality learning opportunities. He mentioned starting reading and math labs for students who might be struggling with the curriculum as a way to keep students from falling behind and losing credits toward graduation. They are also expanding the internship and service learning opportunities to provide all students with the chance to engage in relevant out-of-school activities.

Hurdles to Reform

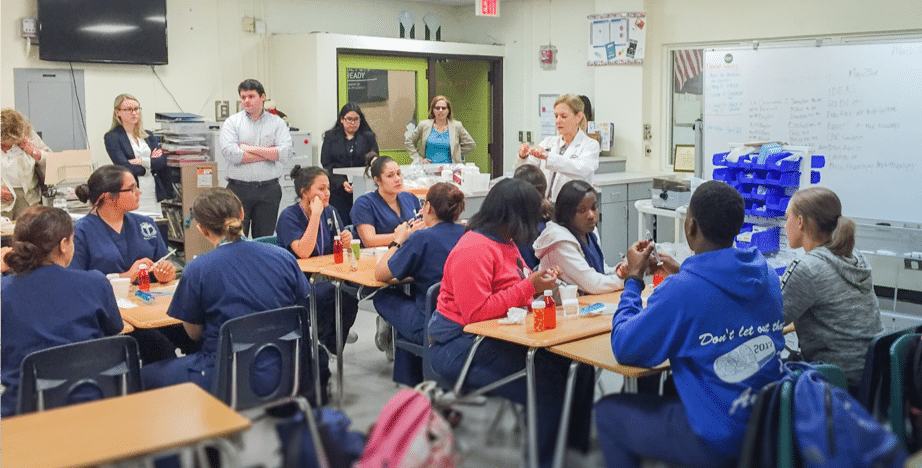

Following a tour of the High School Student Achievement Center, the group was joined by a panel discussion on the hurdles to school reform and the implications of the new state legislation on their reform efforts.

The first issue the panel raised is the lack of state funding specifically designated for programs that are intended for dropout prevention and recovery. “These programs cost money and ‘at-risk’ students need even more resources,” said Ms. Gayle Wiley, School Board Member. The funding formula for alternative students is $512 per students plus administrative costs as compared to $5,000 per student in regular school. The Indiana law requires that alternative students be in school a minimum of three hours per day.

Participants asked the panel whether the new legislation would favorably impact the reform efforts they are undertaking in Shelbyville. “We believe that the new law that increases the legal age of dropouts will help us make the Student Achievement Center mandatory since students will no longer be able to leave at the age of 16 without a formal process,” said Adams, who called the law “common sense.” They are hopeful that the new law, particularly the Fast Track program to reconnect dropouts to high school diplomas, will also provide funding for the types of programs they are hoping to expand in Shelbyville.

Another theme that the panel discussed was the need to change the mindsets and expectations of adults involved with the education of young people, including teachers, parents, and the public at large. “There is still a need to change the mindset of a number of adults who were able to get good jobs and make living wages without a high school diploma,” said Ms. Kim Owens, City Council Member. The panel members agreed that this is no longer the case as the economy in the region continues to change and job opportunities for highly skilled jobs continue to grow. According to Shelbyville Mayor Scott Furgeson, the local economy is shifting and many people are beginning to recognize the need to prepare kids to higher standards and higher skill levels, but we need to continue to champion this since it’s not their grandparents’ economy. Shelbyville’s high-tech and manufacturing industries are growing and many of those jobs require post-secondary training after high school at a minimum.

Mr. Denny Ramsy, Principal of Shelbyville Middle School mentioned that some teachers only want to teach students who “want to be there,” which perpetuates the notion that some young people should be held to high expectations while others should not,” said Ramsy. “This is slowly changing as we continue to look at the data that support high expectations for all kids makes the biggest difference and as we look at what many of our students who are most at risk can accomplish.” Adams and Zobel agreed that changing the mindset of educators is not always easy, but is necessary for reform efforts to take shape.

In addition, many parents send their children to private schools in Shelbyville because their perception of public education is not very good. One reason for the focus on the dropout issue is to bring to light that even a community like Shelbyville can have a dropout problem. This sends a strong message to the rest of the country that they should all examine the data and realize that it’s not just an urban problem. However, it could also alienate the public education system in Shelbyville more, reinforcing ideas that the public schools are hopeless. Mr. Adams is working with school board members and city council to raise the dialogue around the public school system and change the perception. “We want to get the message out that we are no different from the rest of the country in our graduation rates, but that being the same—at the national average—is not good enough for our community and for our kids,” said Adams. “We want them to know that if we work together, we can be a shining light in the state of Indiana and in the nation. When Time magazine comes back in four years to do a follow-up story, we want the story to be that this is a school and a community that came together to address a problem and that we’ve made a difference,” said Adams.

Contact Information

Dave Adams

Superintendent

Shelbyville Central Schools

803 St. Joseph Street

Shelbyville, IN 46176

Business: 317-392-2505 / Fax: 317-392-5737

daadams@shelbycs.k12.in.us

The Honorable Austin Badon

State Representative

3212 Prytania

New Orleans, LA 70115

(504)896-1491

larep100@legis.state.la.us THIS IS WRONG!!!! *******

The Honorable Regina Barrow

State Representative

4305 Airline Highway

Baton Rouge, LA 70805

(225)359-9331

larep029@legis.state.la.us THIS IS WRONG!!!! *******

The Honorable Bob Behning

State Representative

200 W. Washington Street

Indianapolis, IN 46204-2786

317-232-9600

h91@in.gov

Marcie Brown

Education Policy Director

Office of Governor Mitch Daniels

Statehouse

Indianapolis, IN 46204-2797

Business: 317-234-4256

mabrown@gov.in.gov

The Honorable A.G. Crowe

State Representative

195 Strawberry Street

Slidell, LA 70460

(985)643-3600

larep076@legis.state.la.us THIS IS WRONG!!!! *******

The Honorable Adam Ebbin

State Delegate

P.O. Box 41870

Arlington, VA 22204

(703)549-8253

DelAEbbin@house.state.va.us

Sean Eberhart

State Representative

Indiana House of Representatives

2744 E Michigan Road

Shelbyville, IN 46176

Business: 317-398-4910

sean@seaneberhart.com

The Honorable David Ford

State Senator

200 W. Washington

Indianapolis, IN 46204

S19@in.gov

Scott Furgeson

Mayor

City of Shelbyville

44 West Washington Street

Shelbyville, IN 46176

Business: 317-398-6624 / Fax: 317-392-5143

sfurgeson@cityofshelbyvillin.com

Kay Harmless

Director

McKenzie Career Center

Lawrence Early College High School for Science and Technologies

7250 E. 75th Street

Indianapolis, IN

Business: 317-964-8085

kayharmless@MSDLT.k12.in.us

Stanley Jones

Commissioner of Higher Education

Indiana Commission for Higher Education

101 West Ohio Street

Suite 550

Indianapolis, IN 46204-1971

Business: 317-464-4400 / Fax: 317-464-4410

sjones@che.state.in.us

The Honorable Mike Lott

State Representative

691 Hillcrest Loop

Petal, MS 39465

(601)408-2598

msrep104@yahoo.com

The Honorable Joseph McNamara

State Representative

23 Howie Avenue

Warwick, RI 02888

(401)941-8319

rep-mcnamara@rilin.state.ri.us

The Honorable Luke Messer

State Representative

345 West Broadway St.

Shelbyville, IN 46176

(317)517-6818

luke.messer@icemiller.com

Cheryl Orr

Liaison

Indiana Education Roundtable

101 W. Ohio St., Ste. 550

Indianapolis, IN 46204-1971

Business: 317-464-4400 x19

cherylo@che.state.in.us

Jonathan Plucker

Director

Center for Evaluation & Education Policy

509 East Third Street

Bloomington, IN 47401-3654

Business: 812-855-4438

jplucker@indiana.edu

The Honorable Greg Porter

State Representative

3614 N. Pennsylvania St.

Indianapolis, IN 46205

(317)926-1179

gporter@hhcorp.org

Suellen Reed

Superintendent of Public Instruction

Indiana Department of Education

200 West Washington Street

State House, Room 229

Indianapolis, IN 46204

Business: 317-232-6665

sreed@doe.state.in.us

Terry Spradlin

Associate Director

Center for Evaluation & Education Policy

509 East Third Street

Bloomington, IN 47401-3654

Business: 812.855.4438

tspradlin@indiana.edu

The Honorable Brent Waltz

State Senator

PO Box 7274

Greenwood, IN 46142

(317)232-9400

S36@in.gov

Eugene White

Superintendent of Schools

Indianapolis Public Schools

120 E. Walnut St.

Indianapolis, IN 46204

Business: 317-226-4530 / Fax: 317-226-4498

Jeffery Zaring

State Board Administrator

Department of Education

Indiana State Board of Education

Room 229, State House

Indianapolis, IN 46204-2798

Business: 317-232-6622

jzaring@doe.state.in.us

Tom Zobel

Principal

Shelbyville High School

2003 S. Miller Street

Shelbyville, IN 46176

Business: 317-398-9731

tczobel@shelbycs.k12.in.us

Staff

National Conference of State Legislatures

Julie Davis Bell

Group Director

7700 E. 1st Place

Denver, CO 810230

303-364-7700

303-364-7800

julie.bell@ncsl.org

Jennifer Stedron

Program Manager

7700 E. 1st Place

Denver, CO 810230

303-364-7700

303-364-7800

jennifer.stedron@ncsl.org

American Youth Policy Forum

Iris Bond Gill

Senior Program Associate

1836 Jefferson Place, NW

Washington, DC 20036

202.775.9731

202.775.9733 (fax)

Caroline Christodoulidis

Program Associate

1836 Jefferson Place, NW

Washington, DC 20036

202.775.9731

202.775.9733 (fax)

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices

Alex Harris

Senior Policy Analyst

444 North Capitol Street, Suite 267

Washington, DC 20001-1512

Ph: (202) 624-7850

Fx: (202) 624-7827

aharris@nga.org

Local Press

Lawmakers visit Shelbyville school in reform study

Visiting federal lawmakers study dropout issue in Shelbyville