Monica Evans, AYPF Policy Research Intern, and Samaura Stone, Senior Director

As thousands of college students across the country prepare for the holiday season, cram for their final exams, book their travels, and anticipate spending valuable time with their loved ones, there is another reality that many students face, one that is filled with uncertainty. Instead of thinking about what gifts they hope to receive or planning how to spend their well-deserved holiday break, they are pondering questions such as, where they will sleep when their dorm is closed and where they will get their next meal? Unfortunately, these students are not alone as they juggle the additional burdens that come with their pursuit of higher education.

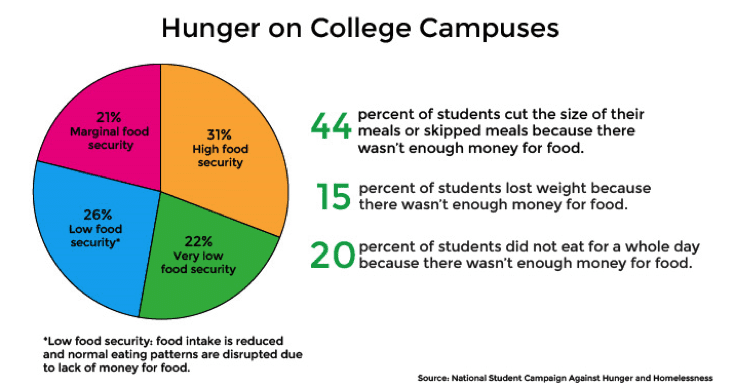

According to a 2016 report published by the National Student Campaign Against Hunger and Homelessness, students experiencing food insecurities account for about half of all students. In 2018, the largest national study ever was conducted by the Wisconsin HOPE Lab to assess the basic needs of college students. The survey was comprised of 43,000 students across 20 states and the District of Columbia, and the results showed that 36% reported facing food insecurity in the past 30 days, 9% reported being homeless in the past year, and 36% reported facing housing insecurity. The most at risk youth for housing and food insecurity are former foster youth. From the same study, 686 students were former foster youth, and 60% reported housing and food insecurity.

There are only a few colleges across the United States that allow their students to stay in the campus dorms for free during the holiday breaks, but while they might offer housing, it often comes with a catch—the cafeterias are typically closed. A recent NPR interview with Ms. Rencher, an Eastern Michigan University (EMU) counselor, who is in charge of a program called Mentorship Access Guidance in College (MAGIC), said she routinely provides students who have experienced foster care, homelessness, or both with snacks throughout the school year and then groceries during the holiday breaks because while the dorms at EMU are fortunately open, the cafeterias are closed. She works with about 20 students to help them figure out where they are going to go and what they are going to eat when campus is closed for two weeks during winter break.

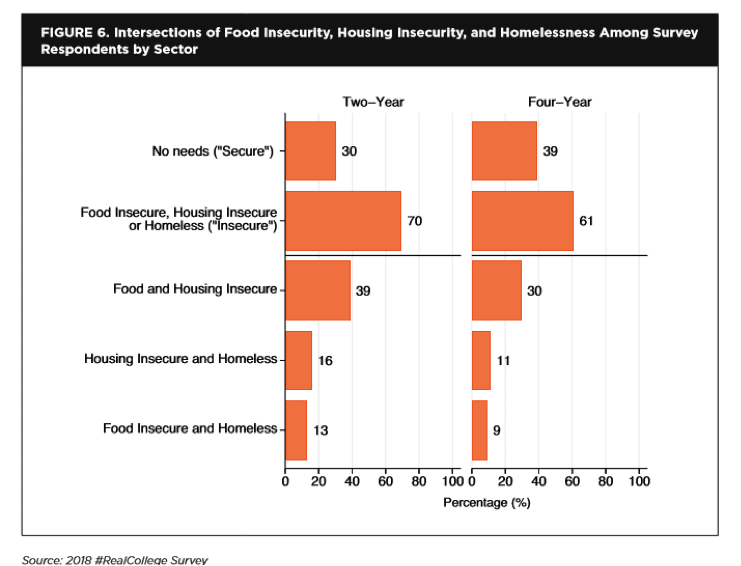

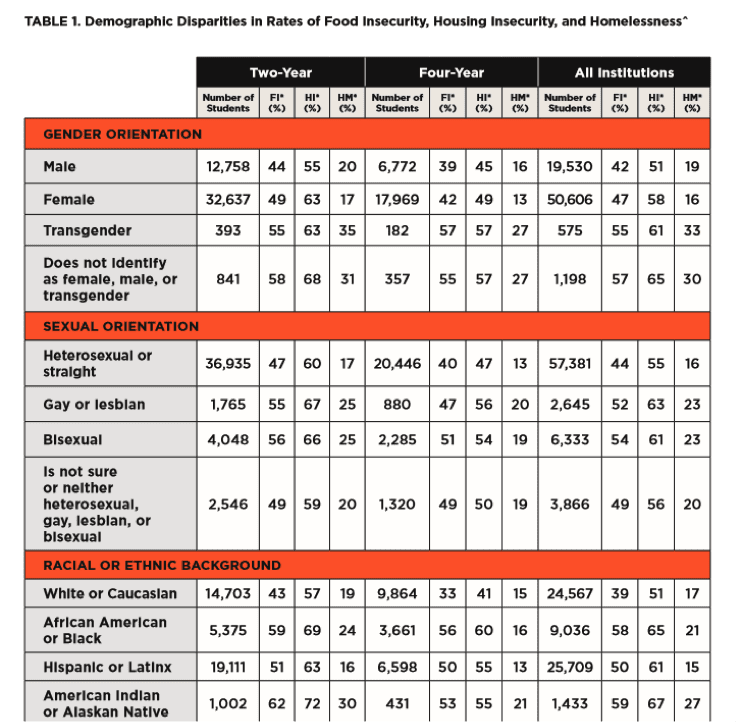

Housing insecurity is typically not a stand-alone issue. In fact, student housing insecurity is often associated with other issues, such as food insecurity or lack of transportation. The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice National Real College survey studied the intersection of food and housing insecurity, as well as homelessness on campus. The survey revealed that basic needs can vary over time and students may experience overlapping challenges throughout semesters. For example, some students might experience food insecurity during the summer and homelessness during the winter. Another point that was highlighted were the extreme disparities by race, gender, and sexual orientation with regard to homelessness and food insecurity. African-American students experienced the highest level of food insecurity at 58%, and Native American students had the highest rate of housing insecurity at 67%. Students identifying as LGBTQ, specifically transgender students, students over 26 years old, and students whose parents did not have a high school diploma also experienced high rates of housing, food, or both insecurities.

*FI stands for the rate of food insecurity; HI stands for the rate of housing insecurity; and HM stands for the rate of homelessness. Source: 2018 #RealCollege Survey

Students facing extra challenges to their education like housing insecurity, homelessness, or food insecurity are seeing the repercussions of these added barriers in their academic achievements. In the same 2018 study listed above, it was reported that more than half of the students who received D’s or F’s in college were food insecure, more than half were housing insecure, and more than one-fifth were homeless. Food insecurity is linked strongly with lower academic achievement and housing insecurity is more strongly linked with poorer attendance, completion, and credit attainment.

Social stigma surrounding college homelessness and food insecurity continues to be a major problem and the main factor hindering students from receiving the resources they need. According to the College and University Food Bank Alliance, there are 163 registered campus pantries across the United States. While the number of food pantries has significantly increased over the years, more than 50% of students at a Midwestern college who self-reported to be food insecure said that they would not go to a campus pantry because they did not want to be served by one of their peers.

Recommendations for Colleges and Universities

1. Offer programs that connect students with host families during the long school breaks. Some colleges around the United States have programs that accommodate international students by connecting them with a host family during school breaks. These same programs could connect homeless, housing/food insecure, or former foster youth students with a host family.

2. Keep dorms open year round with food services provided. At West Chester University in Pennsylvania, there is an initiative called the Promise Program that focuses its efforts on supporting the college’s homeless students and former foster youth students. The program, started by the Office of Residence Life and Housing Services, ensures that their homeless students and former foster youth students have free dorms to stay in during the winter break. In addition, there are winter break shuttles and donated care packages.

3. Implement anonymous food pantries and broaden campus support. Some colleges are looking at creating total anonymity for their students who access their food services. At the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, students don’t need to fill out any paperwork in order to access food from their school pantry. To contribute to the anonymity of the food pantries, there would be call ahead services that allow students to pick up items at a set time without paperwork and also a delivery service that would bring the food and hygiene products to the student’s dorms. Additionally, the services would be moved from one office or department and integrated among campus, allowing for students to have multiple access points while also creating a culture of support and eliminating stigma.

4. Develop Partnerships with key stakeholders. Partnerships with community-based organizations, government, and private sector agencies that are working to tackle housing and food insecurities can lead to innovative solutions. Partnerships can provide additional funding, social services, and staff that can expand campus efforts. For example, Takoma Community College developed a partnership with the Takoma Housing Authority to create the Takoma Housing Assistance Program. This program is the first in the country to provide Housing Choice Vouchers for full-time students.

5. Build Upon State Legislation and Programs. States across the country have increased their efforts to address the issue of homelessness and housing insecurity among college students:

• Several states, including California and Louisiana, enacted legislation that provides homeless and former foster students with a liaison on campus.

• Maryland, Florida, and other states have passed legislation that exempts or grants waivers of tuition to their homeless students.

• Minnesota, California, and Washington allocated budget funds to be given to colleges that have a high homeless student population for emergency assistance, such as housing and student support programs.

Higher education is now a necessity rather than an option and one of the strongest indicators of upward socio-economic mobility for low-income students. There are more resources assisting students as they enter college, but once they become a part of the student body, the services begin to fall short. Housing/food insecurity and homelessness is a national problem that we must address. College breaks and holidays should not create an added barrier for students that are already struggling to succeed. We must ensure that all students, especially those from marginalized and historically underrepresented backgrounds, are allowed the same opportunities to unlock their potential. Education must become the great equalizer, but for that to happen, we have much more work to do. “For these are all our [students] and we will all profit by or pay for what they become.” –James Baldwin

Higher education is now a necessity rather than an option and one of the strongest indicators of upward socio-economic mobility for low-income students. There are more resources assisting students as they enter college, but once they become a part of the student body, the services begin to fall short. Housing/food insecurity and homelessness is a national problem that we must address. College breaks and holidays should not create an added barrier for students that are already struggling to succeed. We must ensure that all students, especially those from marginalized and historically underrepresented backgrounds, are allowed the same opportunities to unlock their potential. Education must become the great equalizer, but for that to happen, we have much more work to do. “For these are all our [students] and we will all profit by or pay for what they become.” –James Baldwin