Mary Nelson, BRIDGES Program Manager, CASA for

Children of DC

I want to tell you the story of two boys, Jim and Tom. Initially their stories sound quite similar, the story of teen boys struggling with their behavior. Yet the stories diverge when different government agencies, and ultimately different systems, intervene. Jim’s story involves the child welfare system, while Tom’s involves the justice system. These interventions trigger different experiences for Jim and Tom. While these stories are hyperbole, they are meant to illustrate how the two systems can approach similar circumstances in a very different way. Ultimately, thinking critically about Jim and Tom’s story can be used as a lens for evaluating the effectiveness of youth-serving systems on the whole.

Jim:

Jim is a 14-year-old boy in Wintertown, Nowheresville. Jim has stolen from his parents, gotten in fights at school, and runs away from home on a semi-regular basis. Jim’s parents were reported to Child Protective Services (CPS) because they refused to allow Jim to come home from school after he was suspended. An in-home case was opened with the Wintertown child welfare agency in hopes of providing community support and interventions. However, after Jim lashed out at home and hit his mom, Jim’s parents dropped him off at the child welfare agency’s office. His parents maintained that they did not want Jim to get in trouble and would not call the police, but could no longer care for him. Jim was taken into care and placed in a group home. Jim has a Guardian ad Litem (GAL) that represents his best interests and an assigned social worker to assist the family in working towards reunification. The main focus is providing Jim’s parent’s with additional parenting skills and supports. Jim and his parents are court ordered to participate in therapy, and Jim is allowed to go home on weekends. Jim’s child and family team is careful to reassure Jim that he is not a bad child; Jim may have some behaviors he needs to work on individually, but his family also has some work to do to make sure his home is safe and supportive for everyone. In court Jim’s judge asks him what he needs to be successful and how his team can best support him. Before Jim’s last court date, he ran away from the group home and did not attend the hearing. While Jim is not required to attend these hearings, he is welcome. Jim’s social worker explained that Jim’s most recent abscondence was likely due to a feeling of frustration at not making much progress towards getting home. All parties are concerned for Jim’s well-being when he runs away, but agree to work on a safety plan instead of punishing him.

Tom:

Tom is also a 14-year-old boy in Wintertown. Tom’s parents are also struggling with his behavior. Tom has stolen money from his neighbors and gotten into fights at home. On one occasion Tom shoved his grandmother, and his parents called the police to intervene. When the police arrived Tom was arrested for assault and detained overnight until he could be seen in court the next day. On the day of court Tom is assigned a defense attorney to represent his stated interests and a case manager to monitor his compliance with any court orders. Tom has a series of hearings to determine the outcome of his juvenile charge. He eventually is released home. His parents come to court, but are somewhat removed from the process. The case manager offers services once to Tom’s parents, but they declined, explaining, “Tom is the problem, not us.” Tom is court ordered to participate in individual therapy, placed on electronic monitoring, and ordered to report to his case manager once a week. His case manager continually asks Tom if he’s, “taking this seriously” or “even understands the consequences of his behavior”. Tom’s parents continue to be frustrated with his behavior and tell him he, “might as well just be locked up”. Tom runs away from home two days before his next court date, but arrives to court on time. Tom’s case manager is recommending that Tom be placed in a group home, a form of non-secure detention. Tom’s defense attorney explains that Tom ran away because he was feeling stressed and unwelcome in his home; Tom felt the need to, “get away for a bit.” Still, Tom’s judge states that if Tom can’t be trusted then his privileges may be taken away. Additionally, Tom needs to take responsibility for his actions. Tom’s judge orders him to be placed in the group home.

For Jim his situation is framed as “not his fault”, and an emphasis is placed on the work his parents must do to make home life safer and more supportive. For Tom the emphasis is placed on his accountability and consequences for his own behavior.

Certainly, I do not mean to imply that experiences like Jim’s never occur in the juvenile justice system, or vice versa with Tom. Yet, in my experience working across the two systems, I have noticed an overall tone and attitude that is reminiscent of Jim’s story in child welfare and Tom’s story in juvenile justice. Tom and Jim’s stories can be used to explore the conceptual underpinnings of each system that may lead to these differing experiences, and the implications.

Conceptual Underpinnings of Systems

The nexus of child welfare is explicitly framed from a context of correcting the deficits of parents and caregivers. The Child Abuse Prevention & Treatment Act (CAPTA) makes clear that the issues to be addressed by these systems are the acts or failures of parents and care givers that result in death, harm or imminent danger to children. Child Welfare Information Gateway, the federal resource bank on child welfare, defines a child welfare system as “a continuum of services designed to ensure that children are safe and that families have the necessary support to care for their children successfully.” From a theoretical standpoint, child welfare can never be about the responsibilities or actions of the child when the very purpose of the system is to course correct the shortcomings of parents or caregivers. Moreover, imbedded in child welfare are deep-rooted principals of the best interest. In fact, every state’s laws require that child welfare courts take a best interest stance to some degree when making decisions for the child.

The juvenile justice system, on the flip side, has evolved with a series of sometimes competing and contradictory priorities including punishment, public safety, incapacitation, and rehabilitation, in addition to considerations of the best interest of the child. Cook County, Illinois, home of the first established juvenile court, states the purpose of the juvenile justice system is to: 1) Protect citizens and the community, 2) Hold youth accountable for crimes, 3) Rehabilitate through individualized assessments and services, and 4) To provide fair hearings and protect legal rights. Here there is a heavy emphasis on correcting the deficits of the child so that the community may be safe from them and they may become productive citizens.

Notably too, in the juvenile court the stated interest of the child is often weighed heavily against the best interest of the child, which some argue is the fallout of the Supreme Court decision in re Gault. Yet, this illustrates another important distinction between the two systems. In juvenile justice the child is the defendant, whose civil liberties must be protected. In the child welfare system, the child is the respondent, and it is the parent’s rights that must be preserved and protected by due process.

These nuances provide a context for understanding why attitudes towards the youth and family may differ between systems. However, it is also worth noting that within the 52 states and the District of Columbia there are hundreds of child welfare and juvenile justice systems that vary in their practices and procedures. Moreover, for both systems there is national recognition of the importance of addressing racial disparities, providing trauma informed services, preventative services, and evidence-based practices.

Why Does it Matter?

Justice & Equity

Especially because of the well-known disproportionalities that exist in both the juvenile justice and child welfare systems, it is important to be vigilant in ensuring such systems promote equity and justice for children and families. If children with similar backgrounds and circumstances are disadvantaged by the happenstance of one system’s involvement over another, it calls into question equity and justice within the individual systems. Yet, in addressing child-serving agencies, we have an opportunity to change the narrative from asking, “How do we care for children who have been abused and neglected?” and “How do we deal with juvenile delinquents?” to “How do we want any child in our community to be treated?”

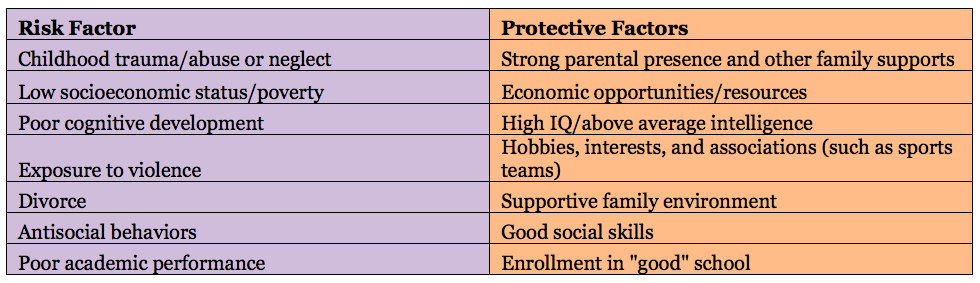

This sentiment is particularly striking when you take into account that the vulnerabilities and requisite protective factors for youth involved in either system tend to be extremely similar. Homelessness, educational concerns, risk of sex trafficking, abuse and neglect, mental health services, and trauma are all discussed on a daily basis by the dedicated professionals serving youth in either system.

Common risk and preventative factors based on comparisons from childwelfare.gov and youth.gov’s juvenile justice section

Exposure to trauma: 80% Youth in JJ; 70% Youth in CW

Mental Health Issue: 70% Youth in JJ; 80% Youth in CW

Performing Below Grade Level: 48% Youth in JJ; 30% Youth in CW

Children and families should have equal access to effective services and resources addressing these common risks, regardless of the system they’ve been designated to. Yet, it may be the case that attitudes towards youth and families, which Tom and Jim illustrate can be impacted by the systems themselves, and change the way that preventative services and interventions are utilized for youth and families. And, because systems are often siloed, it can be hard to know what is and is not working across the whole of youth-serving systems. A just system would not leave outcomes to chance, but would afford the children and families in our communities the greatest opportunities for success.

Critical Evaluations of System Effectiveness

Tom and Jim’s scenarios present a unique opportunity for the child welfare and juvenile justice systems to learn from one another. While most research focuses on data collection and integration when youth or families have contact with both systems, for example, the Child Welfare League of America’s Guidebook for Juvenile Justice & Child Welfare System Coordination and Integration, there is likely benefit in comparing the outcomes of youth in discrete systems with similar needs. By performing a detailed evaluation of each system, including how outcomes for youth deviated or cohere between systems, government and agency leaders could gain valuable insight into how best to provide for the youth and families in their communities.

The lessons learned from evaluating youth serving systems as a whole, as opposed to agency by agency, could fundamentally change outcomes for youth and families. This is an opportunity to ask questions like, “What interventions are working to address shared risk factors like poverty, community violence and educational deficits?” and “What are the values, objectives, and standards that should be upheld in any youth-serving system?”

Likewise, in the case of the crossover youth, youth who have previous or current contact with both systems, it is essential for teaming to take place across systems. This principal is clearly established in the Center for Juvenile Justice Reform’s seminal work the Crossover Youth Practice Model (CYPM). It requires the systems themselves, along with the individual professionals working directly with the youth, to have a clear understanding of each system’s perspectives and priorities, in addition to the procedural aspects of the systems.

In Dallas County, where the CYPM has also been implemented, the Deputy Director of Probation Services, Rudy Acosta, commented that not only has the model improved outcomes for youth individually, but, “has also afforded the opportunity for the respective agencies to truly understand the goals and objectives guiding the daily decisions when working with youth.” Similarly, in Harris County, the individual agencies agreed on the common values that all youth should, “thrive in the areas of wellness, education, and transition to adulthood” and the importance of youth and family engagement. Evidence supports that the CYPM is an effective model for reducing recidivism and facilitating positive interagency collaborations.

What Can You Do?

Armed with the insight of Tom and Jim, I recommend policymakers and government leaders consider the following steps that could improve youth-serving systems overall:

1. Establish formal channels of dialogue across juvenile justice and child welfare systems. Working groups, committees, and coalitions are great forums for discussions to take place regarding how to create equitable and effective youth-serving systems.

2. Audit youth-serving systems as a whole and use this as an opportunity to compare and contrast outcomes between the juvenile justice and child welfare systems. Evaluations can be an effective tool for understanding what is and is not working for children and families in your communities.

3. Seek qualitative data from youth and families to see where youth experiences and circumstances may be the same or different between systems.

4. Take a page from the CYPM book, and establish cohesive values, goals and objectives across youth-serving systems.

Tom and Jim are merely examples of the lens through which youth may be viewed in different systems, and the way that plays out in their individual experiences. But they provide a valuable context for understanding the variation of experiences youth may have when their circumstances really are not so different. This can be a useful tool for learning how best to create systems that provide effective interventions and supports, and also for understanding that the systems we rely on in society to protect our children and families are not perfect. As we continue to strive for just and equitable systems, we need to utilize every tool in our tool kit. Observation and comparison across youth-serving systems may be a powerful tool indeed.