In the age of information, I’m finding simple is better. Information is constantly thrown around about the skills gap, the need to better connect education to employment, and the evolving demand for college and career preparation in the 21st century. After attending this year’s Close It Summit in Chicago last week, I left even more convinced that those of us in the education policy space need simpler messages. Not just “there’s a skills gap” or “the workforce is changing”, but what that means for our nation’s young people and those who work to help them be successful. So, in an attempt to be so 21st century about this, I thought, “what better way to share my key takeaways from the conference than via tweets?” (an idea I got from my colleague and fellow millennial, Jesse Kannam.) Below are my three key takeaways from the Summit.

1) The skills that make you a good employee are the same skills that make you a good person and a good citizen.

As noted by Jeffrey Selingo at the conference, and as discussed in his book There is Life After College: “In many ways the modern work world looks a lot like a pre-school classroom where curiosity, sharing, and negotiating are front and center.” The principles of curiosity and negotiation sound a lot like the tenets of social and emotional learning (SEL). The personal and interpersonal awareness required to interact as a four year old isn’t very different from the workplace skills that are so in demand. According to Selingo’s research, the five skills employers most want in their employees are curiosity, creativity, digital awareness, contextual thinking, and humility. To be sure, SEL has benefits far beyond developing competent future employees. But if we in the education space are trying to better connect our efforts to what is needed in the workforce, maybe we need look no further than a kindergarten classroom.

2) Is the skills gap partially just a gap in communication?

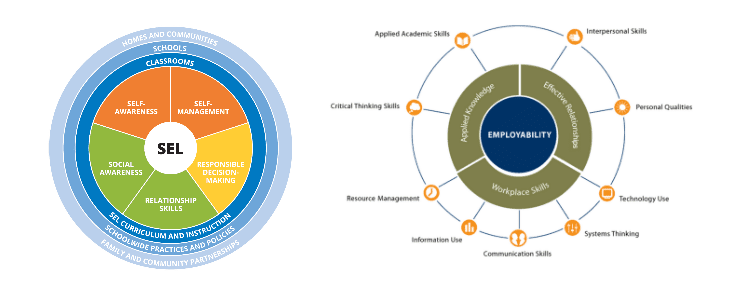

A discussion about the skills gap inevitably makes me think about language. As discussed above, many of the competencies desired by employers are already prioritized in classrooms that focus on the social and emotional development of young people. I can’t help but wonder, then, if at least part of the skills gap we’ve all heard so much about can be attributed to inconsistent language between the education and workforce sectors. For instance, take a look at the SEL framework as compared to the employability skills framework below. Although the intent, design, and implementation of SEL and workforce development may be different – as is the language used in these frameworks – there is certainly alignment. For example, “relationship skills” and “social awareness” in the SEL framework are similar to “interpersonal skills” and “communication skills” in the employability skills framework. Can we, as a field, come up with a better way to communicate to employers the skills that young people obtain in adolescence and how those translate into the skills they’ll need as employees?

From left to right: SEL Framework and Employability Framework

3) Stop looking at work as an obstacle to success in secondary and postsecondary education.

Particularly in the higher education space – though I think it also applies to the way we think about high school – work can be seen as detracting from learning. But as we know from the success of internships in preparing young people for college and careers, work is not only not a distraction, but an asset to students’ skill development. Even part-time jobs in high school and college that aren’t associated with official internships, such as jobs in the service industry or retail, can help young people get a better understanding of professionalism and other workplace expectations. Relationship building, self-awareness, problem solving – all of these things are important on the job and, I’d argue, are necessary for student learning early on and throughout their academic trajectories.

This brings me back to “tweet” #1 – the connection between the modern workplace and the classroom environment. If strong SEL in the classroom can help young people develop into better employees in the future, and if work-based learning can help young people become better students and citizens, there’s absolutely no reason the education and workforce sectors shouldn’t more intentionally align. Maybe we just need to start speaking the same language.